KEY POINTS

• People of color own a small share of all businesses but they have grown substantially in number.

• The economic challenges of the pandemic may undo the growth in the number of businesses owned by people of color.

• Businesses owned by people of color are concentrated in vulnerable sectors and are relatively small, making it more difficult to survive the economic impacts of COVID-19.

June 2020 — Recent analysis demonstrates that communities of color are disproportionately suffering the health impacts of COVID-19. In Milwaukee County, 29 percent of the population is Black or African American yet Black or African Americans represent 43 percent of COVID-19-related deaths1. Much like the poor health outcomes from COVID-19 are disproportionately suffered by people of color, the economic costs are likely also inequitably distributed across racial and ethnic groups.2

The impact on business owners is one way to evaluate these economic impacts and the costs across racial and ethnic groups. Safer-at-home orders and social distancing have had especially dramatic consequences in some sectors. Retail; Arts, Entertainment, and Recreation; Accommodation and Food Services; and Other Services are among those most impacted (Ding and Sanchez 2020, Van Dam 2020). For many business owners in these sectors, the economic consequences of COVID-19 are dire as they have lost sales, employees, and suppliers. Those in the healthcare sector have also been deeply impacted, though in different ways. Healthcare providers are straining to meet the care needs in some regions, while in others they risk financial trouble due to the overall decline in procedures which has negatively impacted cashflows. If businesses owned by people of color are concentrated in these vulnerable sectors, we might expect that they are especially likely to be struggling with the impacts of COVID-19.

Source: Survey of Business Owners 2012

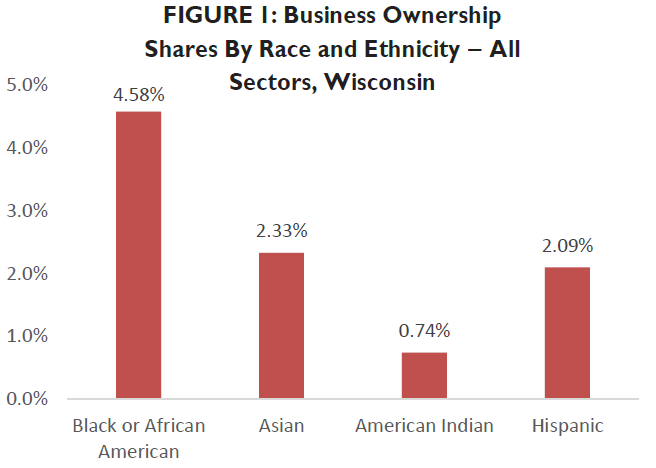

With this vulnerability in mind, COVID-19 has the potential to exacerbate existing disparities in business ownership. As shown in Figure 1, people of color represent relatively small shares of all business owners in Wisconsin. With the exception of Asian business owners, these business owner shares have been shown to be disproportionately small relative to their population shares (Sexton, Hammer and Conroy, 2019), suggesting that there are already barriers to business ownership for people of color apart from challenges created by the pandemic.

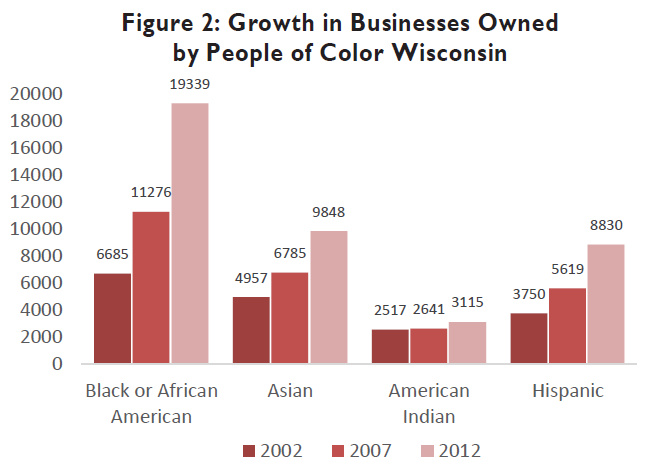

Even though businesses owned by people of color represent disproportionately small shares of all businesses, there have been gains. In number, they have grown substantially since the early 2000s. As shown in Figure 2, the number of Black or African American-owned businesses nearly tripled from 2002 to 2012. The number of Hispanic-owned businesses more than doubled during the same time period. The number of Asian Owned businesses nearly doubled. With the most modest growth, American Indian Owned businesses grew by 25%.

Source: Survey of Business Owners 2012, 2007, 2002. Secondary Sources available at: https://www.mbda.gov/sites/mbda.gov/files/migrated/filesattachments/State_Minority_Business_Enterprises_2007Data.pdf (2007) and https://www.mbda.gov/sites/mbda.gov/files/migrated/filesattachments/Wisconsin_Profile.pdf (2002)

If large shares of these business owners are facing the negative impacts of the pandemic, it may eliminate the growth of these businesses and cause hardship in Wisconsin’s communities of color. For example, even if there are just a few thousand American Indian-owned businesses in Wisconsin but 75% are in the Accommodation and Food Service sector, the pandemic could result in most American Indian-owned businesses closing. This potential loss of businesses is especially costly as entrepreneurship is a known vehicle for wealth creation—an especially important mechanism in economically disadvantaged communities (Pender et al. 2012).

Source: Survey of Business Owners 2012

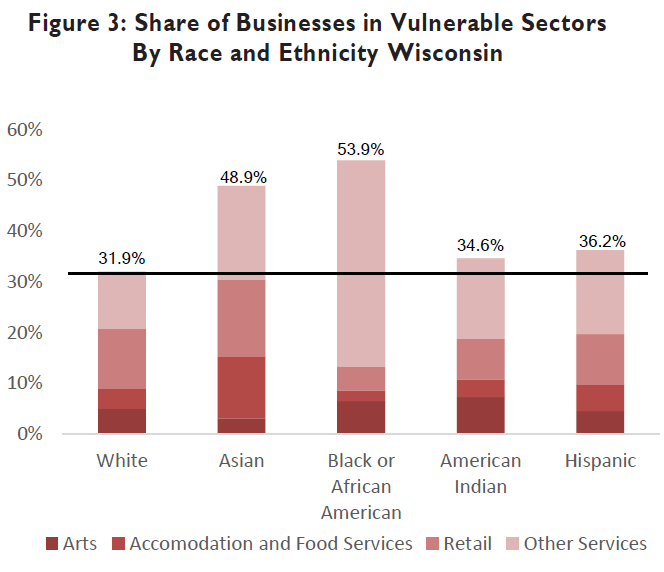

As shown in Figure 3, nearly 32% of White-owned businesses are in vulnerable sectors with the largest shares in Retail and Other Services. Other services is a diverse category that includes equipment and machinery repair, dating services, laundry and dry cleaning, and pet care services among others. All other racial and ethnic groups considered have larger shares of businesses in these vulnerable categories. More than half of businesses owned by Black or African Americans in Wisconsin are in the Arts, Accommodations and Food Services, Retail, and Other Services sectors combined—more than any other racial or ethnic group. Asian business owners are similarly concentrated with nearly 49% of their businesses in these sectors. American Indian and Hispanic business owners own 35% and 36% (respectively) of their businesses in these sectors.

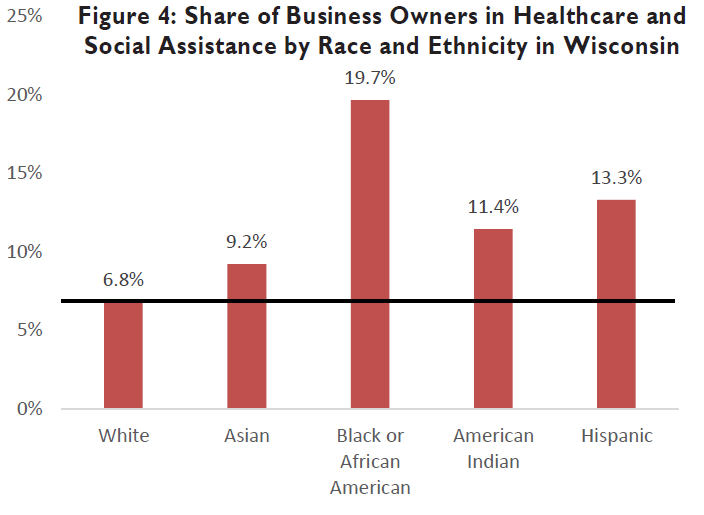

Though healthcare is impacted differently than the service sectors described above, people in these sectors also face challenges. The Healthcare and Social Assistance sector includes social workers as well as home health aides, for example, a quickly growing occupation. As healthcare puts workers at the frontlines of addressing the pandemic, the potential for exposure to illness as well as a demanding schedule may add stress to people in these industries. Conversely, some hospitals, unable to continue with procedures and in areas of low COVID impact, have struggled with revenue and even laid-off workers. Interestingly, compared to the racial and ethnic groups considered here, just 6.8% of White-owned businesses are in Healthcare and Social Assistance (Figure 4). Nearly 20% of Black or African American-owned businesses are in this sector, followed by Hispanic and American Indian business owners who own 13% and 11% of their businesses in this sector.

Source: Survey of Business Owners 2012

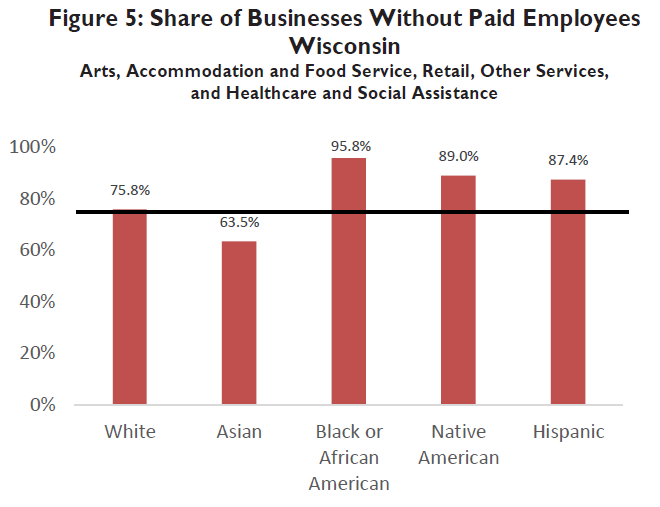

In addition to business owners of color having large shares of their businesses in vulnerable sectors, they also tend to run smaller businesses putting them at greater risk for struggling during the pandemic. Without cash reserves to flexibly manage expenses when sales drop, these business owners may have a harder time weathering the economic slowdown. They may also lack the in-house expertise of accountants and lawyers to help them navigate the business support programs such as those offered by the federal government. Language barriers and a lack of technical assistance can also make it more difficult for business owners of color to use these resources. Due to weaker relationships with key people in the business community, they may also lack the informal connections to quickly access information and resources during times of crisis (Conroy and Weiler, 2019).

Source: Survey of Business Owners 2012

The relatively small size of businesses owned by people of color is shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5. With the exception of Asian-owned businesses, people of color are more likely to run a nonemployer business, meaning they run the business by themselves or with unpaid employees such as family members. In these vulnerable sectors, close to 80% of white-owned businesses are nonemployers whereas nearly 96% of Black-owned businesses in these categories have no employees.

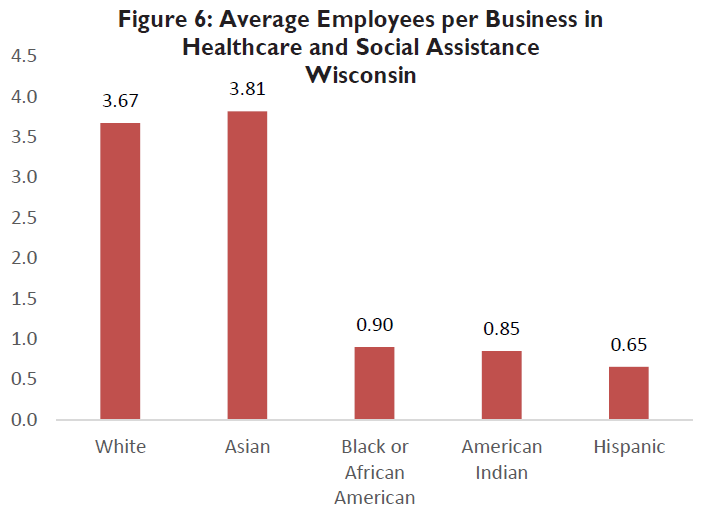

The differences in size are particularly evident in healthcare (Figure 6), where White-owned businesses have more than three times as many employees on average compared to those owned by African Americans, American Indians, or Hispanics. In Figure 6, a value below one is indicative of the large shares of businesses with zero paid employees.

Source: Survey of Business Owners 2012

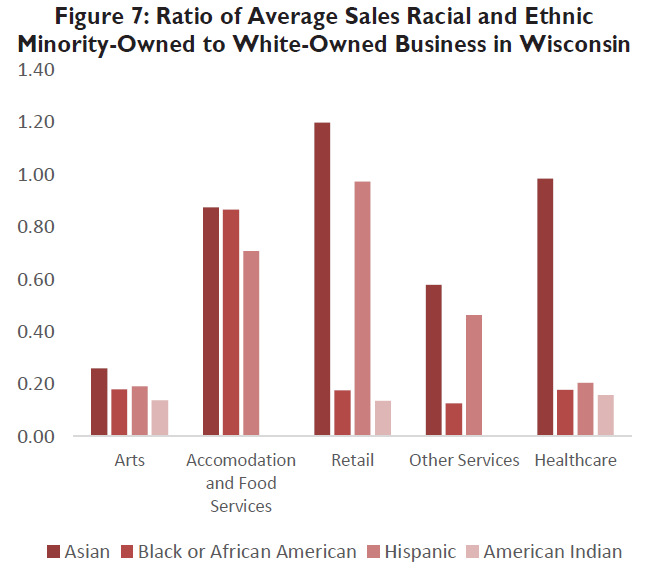

In addition to measuring size with employment, we can measure size with sales. Figure 7 shows the ratio of earnings in the typical firm owned by a racial or ethnic minority to earnings in a typical White-owned firm. A value less than one means the average White-owned business earns more than the average business in the same sector owned by a person of color. A value greater than 1 would suggest the opposite—the average business owned by a person of color earns more than the typical firm owned by a White person.

In the Arts sector, businesses owned by entrepreneurs of color earned sales equal to roughly 20 cents per dollar earned in the average White-owned business. In Accommodation, businesses owned by Asian, Black, Hispanic, or American Indians earned between 65 and 85 cents in sales for every dollar earned by the average White-owned business. In general, across all sectors, Asian business owners face the smallest differential meaning their average earnings are close to that of White business owners. In Retail, the average Asian-owned business even out-performed the average White-owned business, earning nearly $1.20 for every dollar earned in a typical White-owned business. However, across all other sectors and races, businesses owned by people of color earn less on average than White-owned businesses.

Source: Survey of Business Owners 2012

Taken together, these figures suggest that for business owners of color, the pandemic may be especially challenging. Though they own a relatively small share of total businesses, a disproportionate number of their businesses are in the sectors under the most strain right now. In addition to owning businesses in vulnerable sectors, business owners of color also tend to run smaller businesses as measured by employment and sales. At these small sizes, business owners may not have the cash reserves to sustain themselves during a downturn. This means that while all business owners face challenges ahead, business owners of color are particularly susceptible to the ramifications of the pandemic given their industries’ proximity to the disease itself and to the economic downturn, as well as the overall volatility of running a small business.

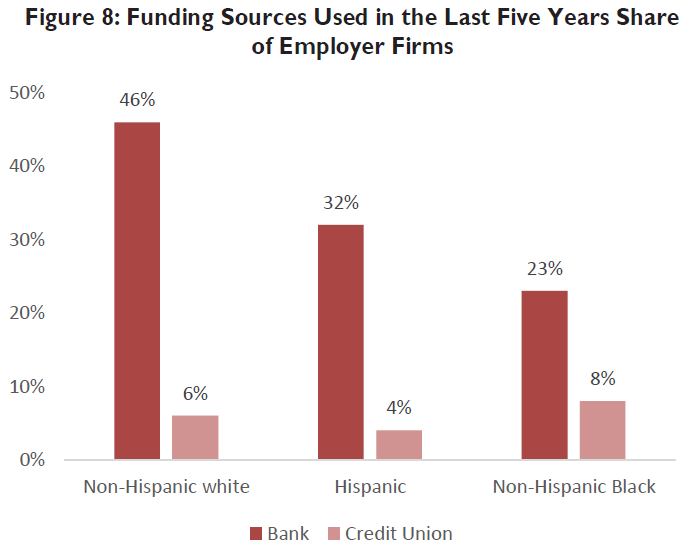

To compound the challenges for these business owners of color, the structure of current Federal programs systematically disadvantages them (Center for Responsible Lending). For example, these programs, such as the Paycheck Protection Program, are largely administered by financial institutions that are less likely to serve people of color (Figure 8). By earning banks larger fees, the program also incentivizes service to large businesses which are less likely to be owned by a business owner of color. Lastly, the program prioritizes those with existing banking relationships. Thus, because business owners of color have less frequently used banks as a funding source in the past, they are likely at a disadvantage in securing these loans and grants. Some of the strategies to address these systematic gaps and target resources to businesses owned by people of color include access to direct and tailored support, multi-lingual interpretation/translation, channeling funds through organizations such as Community Development Financial Institutions or administering programs at the state or federal level, and setting mandates and guidelines for financial services to underserved communities.

Source: Federal Reserve Banks. (2020) Small Business Credit Survey: 2020 Report on Employer Firms. Available at https://www.fedsmallbusiness.org/medialibrary/FedSmallBusiness/files/2020/2020-sbcsemployer-firms-report.

As we work toward economic recovery for individuals and our communities, entrepreneurship is an important component. At the individual level, business ownership can be a vehicle for wealth creation, an especially important mechanism for economically disadvantaged communities. As we see businesses owned by people of color close, economic gaps may only get larger. Further, entrepreneurship is an important part of vibrant, healthy economies and job creation in particular. To the extent that there are ways to support the breadth of entrepreneurs, the better the state will be positioned for a strong rebound.

Endnotes

1 COVID-19 statistics as of June 9, 2020: https://county.milwaukee.gov/EN/COVID-19

2 The categories of race considered here are Black and African American, Asian, and American Indian or Native Alaskan (“American

Indian” going forward). The category of ethnicity is Hispanic. Racial and ethnic categories are not mutually exclusive.

References

Center for Responsible Lending. The Paycheck Protection Program Continues to be Disadvantageous to Smaller Businesses, Especially Businesses Owned by People of Color and the Self-Employed. May 19, 2020. Available at https://www.responsiblelending.org/sites/default/files/nodes/files/researchpublication/crl-cares-act2-smallbusiness-apr2020.pdf?mod=article_inline

Conroy, Tessa, & Weiler, Stephan. (2019). Local and social: entrepreneurs, information network effects, and economic growth. The Annals of Regional Science, 62(3), 681–713. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-019-00915-0

Ding, Lei and Sanchez, Alvaro. What Small Businesses Will Be Impacted by COVID-19? April, 2020.

Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia. Available at https://philadelphiafed.org/covid-19/covid-19-equity-in-recovery/what-small-businesses-will-be-impacted

Federal Reserve Banks. (2020) Small Business Credit Survey: 2020 Report on Employer Firms. Available at https://www.fedsmallbusiness.org/medialibrary/FedSmallBusiness/files/2020/2020-sbcs-employer-firms-report.

Flitter, Emily. Black-Owned Businesses Could Face Hurdles in Federal Aid Program. The New York Times. April 10, 2020. Available at https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/10/business/minoritybusiness-coronavirus-loans.html

Pender, John, Marre’, Alexander, and Richard Reeder. (2012). Rural Wealth Creation Concepts, Strategies, and Measures. United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Economic Research Report Number 131.

Popken, Ben. Why are so many black-owned small businesses shut out of PPP loans? NBC News. April 29, 2020. Available at https://www.nbcnews.com/business/business-news/why-are-so-many-blackowned-small-businesses-shut-out-n1195291

Van Dam, Andrew. Crisis begins to hit professional and public-sector jobs once considered safe. The Washington Post. April 30, 2020. Available at

https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/04/30/jobless-claims-industry/