December 2018 — With unemployment rates at historical lows and many employers having difficulty finding workers to fill their open positions, policymakers and employers alike are looking for available labor. In Wisconsin, the labor force participation rate is already well above the national average. Given the age structure and historical trends identified by Kures, Deller, and Conroy 2018 , raising the labor force participation rate further may require careful evaluation of the current constraints on labor availability. These constraints on labor force participation may include training or education mismatches, a lack of transportation, health limitations, or having a criminal record. In addition, finding affordable, reliable, high-quality childcare can be essential for working parents.

Women’s work choices, in particular, seem to be acutely impacted by the responsibility of childrearing and securing childcare (Conroy 2018; Bivens et al. 2016).

In Figure 1 we show a correlation between the prime age (25-54 years old) female labor force participation and children under age five per prime age female for all Wisconsin counties. We choose children under age five because, before school age, young children are likely to require full-time care in some form. The figure indicates that women’s labor force participation is inversely related to the number of children under age five per female. This relationship suggests that women often leave the labor force with the onset of childrearing responsibilities.

While many women prefer to leave the labor force so they can provide full-time care, there may be a subset of women that would prefer to work some amount but the limitations of finding high-quality childcare keep them from doing so.

While women do seem to be particularly affected by children and childcare, this issue affects entire households. As gender roles are shifting, father figures are likely also sensitive to the issue of childcare in their work choices. Yet this for males appears to be subtler. In Figure 2 we show the correlation between prime age (25-54 years old) male labor force participation and children under age five per male. The figure indicates a slightly positive relationship; as the presence of young children increases, males join the labor force. Taken together, Figures 1 and 2 suggest that, in Wisconsin, many households may be structured with a male breadwinner and female childcare provider. In fact, in every state, mothers of children under age six are less likely than fathers to be in the labor force (IWPR, 2015).

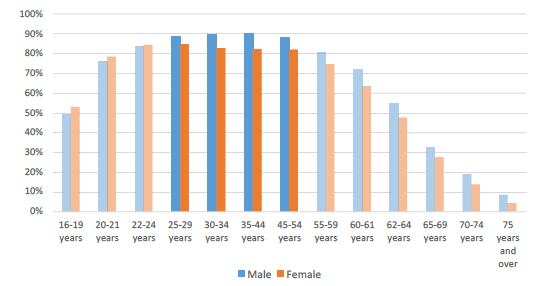

Certainly, every household needs to make the work and childcare choices that are best for them, but there may be some households where an adult who is currently caring for children would prefer to work some amount if they had a good childcare option. In such a case, enhancing local childcare options would expand the labor force. The potential for enhanced childcare to expand the labor force is easily evident if we compare male and female labor force participation rates. Young women and men under age 25 participate in the labor force at nearly equal rates, with women even slightly exceeding men in these early years (Figure 3). Beginning at age 25, however, female labor force participation rates drop below male rates and never reach equality in older cohorts. If prime age (25-54 years old) female labor force participation increased to the level of male labor force participation, there would be an additional 72,000 women in the labor force in Wisconsin.

Of course, it is unlikely that all 72,000 of these “missing female workers” would choose to work more given a desirable childcare option, but it does suggest that there is a relatively large pool of workers to consider. Further, this pool of female workers is likely relatively well-educated given that a larger share of women than men hold a bachelor’s degree in Wisconsin’s younger cohorts (Conroy, Kures, and Deller, 2017). Recent research shows that while young children have a negative effect on regional labor force participation for women, childcare availability has an offsetting positive effect on both female labor force participation and female entrepreneurship (Conroy 2018). If even a fraction of the women who are not in the labor force are affected by childcare, it may be worth policymakers, community leaders, and employers considering the local childcare offerings.

Figure 3: Labor Force Participation by Age Category and Gender (Wisconsin)

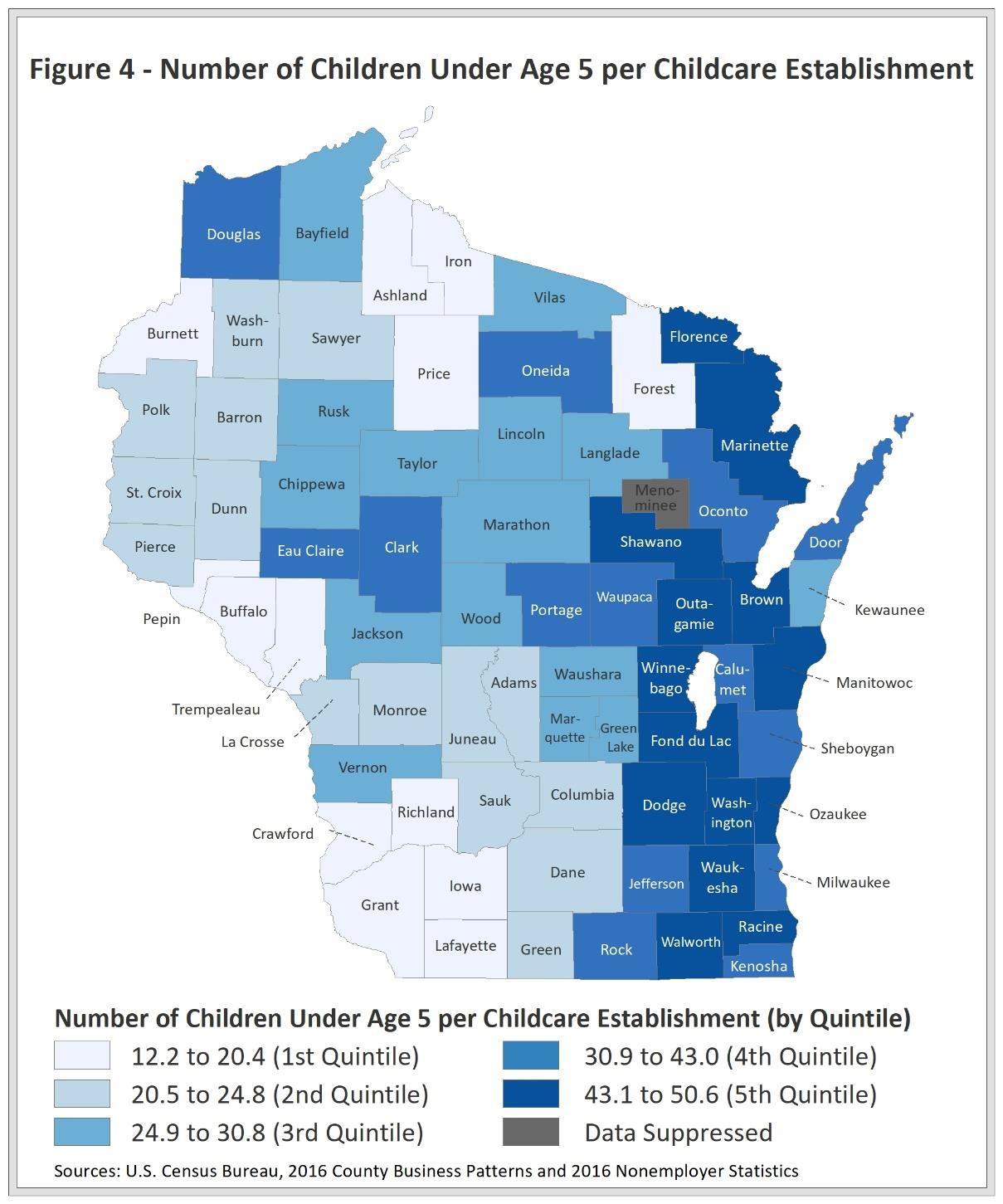

In Wisconsin, there are roughly 6,300 childcare providers including both larger childcare establishments that have at least one employee (25% of providers) and smaller sole provider entities that have no employees, also called “nonemployers” (75% of providers). The availability of these providers does vary substantially across the state. Figure 4 shows the number of children under age five per childcare establishment in each county. As evidenced by the number of children in each county per childcare provider, childcare needs likely well exceed current availability of formal childcare centers in many areas, especially where the majority of providers are small scale individual providers. Families must then rely on their networks and informal arrangements, not included in the graphic, for childcare services. While many such arrangements can be great to support working parents, the lack of formal childcare centers could still be a constraint on families. The Institute for Women’s Policy Research conducted a study of child care for the entire U.S. and found that while childcare varies greatly across the U.S., all states under-provide care for children under age five based on cost, enrollment, and policies to support pre- kindergarten care (IWPR, 2015).

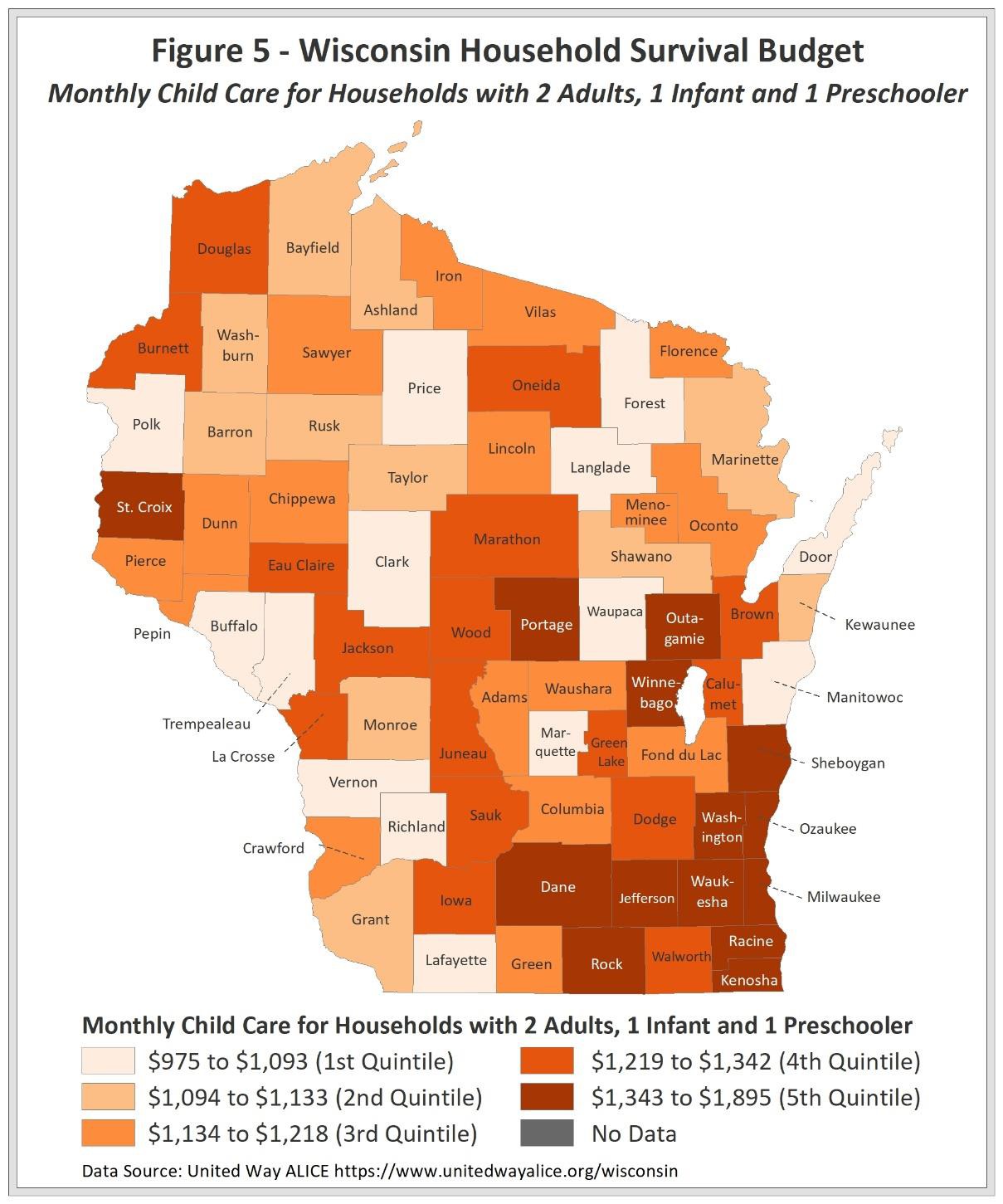

Even if childcare is available, it can be cost prohibitive. One estimate of childcare cost indicates that, in Wisconsin, childcare for a four-year old is between $8,000 and $9,500 annually (“Child Care in State Economies”, 2015), equal to $660-$800 per month. Another study by United Way estimates that childcare in Wisconsin costs $1,231 dollars per month for a family of four with an infant and preschool-age child operating on a bare-minimum budget in 2016 (ALICE, 2018). For a family earning the median household income for Wisconsin of $56,811 in 2016, these estimates suggest that childcare can be in the range of 14-26% of their monthly gross income. By county, estimates of the cost of childcare for a family of two adults, one infant, and one preschool-age child operating on a bare-minimum or “survival” budget are shown in Figure 5 (ALICE, 2018). These estimates may be high in that having an infant or more than one child will increase costs, however, they are conservative in the sense that these reflect a household facing a relatively constrained budget.

Though not costless or easy to address, support for affordable, stable, high-quality childcare options has potential to generate many benefits that go beyond increasing the labor supply:

- Good for Workers. Affordable, high-quality, reliable childcare gives adults with families the option to pursue work or education opportunities and thereby increase their income.

- Good for Employers. Enhancing childcare has the potential to expand the labor force at a time when many employers are finding it hard to fill positions. Further, retaining current employees once they have children to look after can save recruitment and training costs. With their children in reliable, affordable, high-quality childcare, adults are more productive at work through increased hours, missing fewer days, experiencing less stress, and even the option to pursue additional training (Bartik 2011). The notion of “presentism” comes into play: workers may be present at work but are not as productive as possible due to worries (stress) over the safety and care of their children in less than optimal childcare situations.

- Good for Children. Childcare is a setting for early childhood development. Quality childcare can enhance early childhood development and support individual outcomes through adolescence. Several studies have shown that investments in early childhood development are linked to higher test scores and graduation rates, as well as enhanced soft skills (Heckman 2005) and a lower propensity for crime (Rolnick and Grunewald 2003).

- Good for Communities. Support for early childhood development, such as high quality childcare has widespread economic development benefits in that investing in human capital through childcare programs results in a more educated future workforce, and, as previously mentioned, lower crime rates (Rolnick and Grunewald 2003). In addition to these longer-term benefits, each dollar spent on childcare programs will get a roughly $2 return on investment (Warner 2009; Bartik 2011) as measured by income and jobs for residents.

While we are best able to measure the quantity or availability of childcare in the state, the number of providers is just one dimension of the issue. The most successful approaches to childcare will also incorporate quality and cost. Quality is essential for generating the childhood development benefits. Cost must be addressed so that families, many of whom have not seen real wage increases in decades, can afford this care (DeSilver 2018). The multifaceted nature of childcare means support and solutions will likely benefit from comprehensive approaches that incorporate workers, employers, and local leaders.

Already communities in Wisconsin are developing innovative solutions to childcare. In Vernon County on the western edge of Wisconsin just south of La Crosse, Organic Valley and Vernon Memorial Healthcare with several other employers have come together to create a shared services network (Kirwin 2018). With grant support from the Medical College of Wisconsin, they have created a system for shared services and shared costs that helps keep childcare providers in business. They also have plans for a community supported relief squad that will provide backup staff in the event providers are unable to provide services. Such an initiative demonstrates how different players can collaboratively support stronger childcare at the community level and serve as one example for communities interested in working on this issue.

References

Bartik, T. (2011). Early childhood programs as an economic development tool: Investing early to prepare the future workforce. In O. Little, S. Eddy, & K. Bogenschneider (Eds.), Preparing Wisconsin’s youth for success in the workforce (Briefing Report No. 31, pp. 27-40). Retrieved from https://www.purdue.edu/hhs/hdfs/fii/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/s_wifis31c03.pdf

—(August 2015) “Childcare in State Economies.” Produced by Region Track, Inc. commissioned by the Committee for Economic Development.

Bivens, Josh, Emma Garcia, Elise Gould, Elaine Weiss and Valerie Wilson (2016). “It’s time for an ambitious national investment in America’s children.” Economic Policy Institute, Washington DC.

Conroy, Tessa. (2018). “The Kids Are Alright: Working women, Schedule Flexibility, and Childcare Availability.” Regional Studies.

Conroy, Tessa, Matt Kures, and Steve Deller. (2017). “Shifting Wisconsin Labor Resources: A view of Educational Attainment” The Wisconsin Economy. Study Series No. 4

DeSilver, Drew. (Aug 2018). “For most U.S. workers, real wages have barely budged in decades.” Pew Research Center. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/08/07/for-most-us-workers-real-wages-have-barelybudged-

for-decades/

Heckman, James. (2005) Interview for The Region. https://www.minneapolisfed.org/article/2005/interview-with-james-heckman

Kirwan, Hope. “Wisconsin Employers Supporting Local Child Care To Attract, Maintain Workers.” Wisconsin Public Radio. November 27, 2018.

Rolnick, A. J., & Grunewald, R. (2003). Early childhood development: Economic development with a high public return. Fedgazette, 15(2). Minneapolis: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Retrieved from http://www.minneapolisfed.org/publications_papers/pub_ display.cfm?id=3832

— (2018). ALICE Report: Wisconsin. United Way. https://www.unitedwayalice.org/wisconsin

Warner, Mildred. (2009). “Child Care Multipliers: Stimulus for the States.”

Download Article

WIndicators: The Role of Childcare in the Labor Market: A Long-Run Perspective

WIndicators: The Role of Childcare in the Labor Market: A Long-Run Perspective Early Care and Education in Wisconsin: Challenges and Opportunities

Early Care and Education in Wisconsin: Challenges and Opportunities WIndicators Volume 3, Number 5: Are the Kids Alright? Women, Work, & Childcare

WIndicators Volume 3, Number 5: Are the Kids Alright? Women, Work, & Childcare February 6, 2020 Lunch N Learn: Getting Access to Childcare: Why? How? and Who to Work With?

February 6, 2020 Lunch N Learn: Getting Access to Childcare: Why? How? and Who to Work With?