KEY POINTS

• The burden of childcare appears to driving women out of the labor force.

• For women, childcare is a more significant factor in employment choices than it is for men.

• There is evidence of a gender gap in understanding the impact of childcare on women’s careers.

November 2020 — Childcare was a challenge for parents before the pandemic and has only become more difficult in recent months. During the pandemic, as much as 60% of childcare providers closed and stopped providing childcare (Bipartisan Policy Center, 2020). While many of those closures were temporary, a recent state-level study estimates that, in absence of additional aid, 30% of the childcare supply in Wisconsin could be permanently lost if providers are closed for more than two weeks without revenue due to COVID-19 (Center for American Progress, 2020). That’s equivalent to more than 41,000 childcare slots.

The challenge of childcare has been compounded this fall as many school districts have elected to go online or offer hybrid models that still require some amount of at-home learning due to COVID-19. Consequently, even young school-age children are in need of at-home supervision and care. For parents and those raising young children, these changes mean caring for their kids at home as well as managing school schedules of online and hybrid models, play dates in pods, specific care for medically complex children, finding a spot in a child care facility if possible, knowing the hours and safety requirements of those facilities, and finding an alternative arrangement if childcare has to close due to COVID-19.

Virtual learning and less dependable (or an entire lack of) childcare precipitated by the COVID-19 pandemic has been a growing challenge—especially for women. For many families, there is little choice but for kids to be at home with an adult care provider, and often that adult is a mother, older sister, aunt, or grandmother. That may mean these women have to leave their job or go part time as caretaking is a significant factor in women’s employment patterns (Chrisnacht and Sullivan 2020). Women are more likely to adjust their work to meet childcare needs because of their role as primary caregivers, but the choice may also be economic (Gurley-Calvez, 2009, Parker and Wang 2013). If one adult has to stay home, often it is the lower earner—that is usually a woman (Graf et al, 2019). The evidence so far suggests that these circumstances are making it difficult if not impossible for many women to maintain full time employment.

To gain insights into how the COVID-19 pandemic may be disproportionately impacting women with children, we explore two different sets of data in this WIndicator. First, we explore trends in women’s labor force participation rate at the national level. We focus on the national level because the national data are the most current. Second, we draw on the most recent survey conducted by the Division of Extension at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. As discussed in more detail below, results from the survey indicate the responsibility of caring for children is indeed more squarely on the shoulders of women. The responses indicate that COVID-19 has made everything about raising children harder across the board including (1) paying for daycare, (2) affording healthy food, and (3) affording health care. The rates of difficulty resulting from the pandemic are alarming for both women and men, though women consistently reported higher levels of difficulty compared to men.

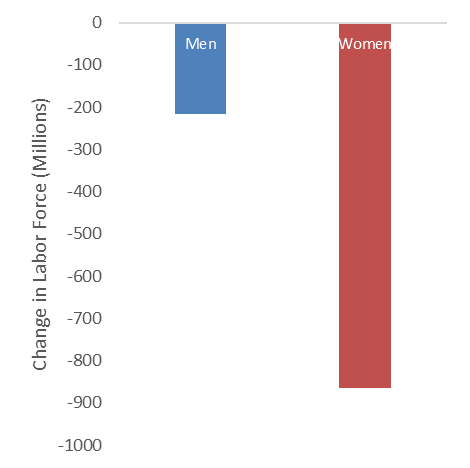

Labor Force Participation

One near term effect of women needing to take on more childcare responsibility is a substantial exodus of women from the labor force, meaning they are neither employed nor looking for work. Women are tasked with more care work than men in the average home and evidence suggests women are more likely to be the margin of adjustment when a household needs change (Gurley-Calvez, 2009, Parker and Wang 2013, Black et al. 2014). That means they are the ones more likely to adjust their work life—often by going part time, or leaving work—in order to provide care and support schooling for children at home while men’s employment situation more likely remains constant. The data already suggests this may be happening. From August 2020 to September 2020, the labor force declined by nearly 1.1 million workers nationally, but the majority of those workers who left were women—about 4 women left the labor force for every one man (Figure 1). This means that women have stopped working and are not seeking work at a rate four times higher than men.

Figure 1: Change in Civilian Labor Force, Age 20 years and over, August 2020 to September 2020

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Table A-1. Household Data. Available at https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf

With women leaving the labor force, perhaps it’s not surprising that the female unemployment rate has come down. In September 2020, the female unemployment rate was 7.7%, down from 8.4% the month prior. We might typically hope that a lower unemployment rate means the employment situation for women is improving, but when it’s driven by women leaving the labor force, that’s not necessarily the case. This decline hides what is happening for women due to COVID: they are often faced with choosing between work and caring for their children.

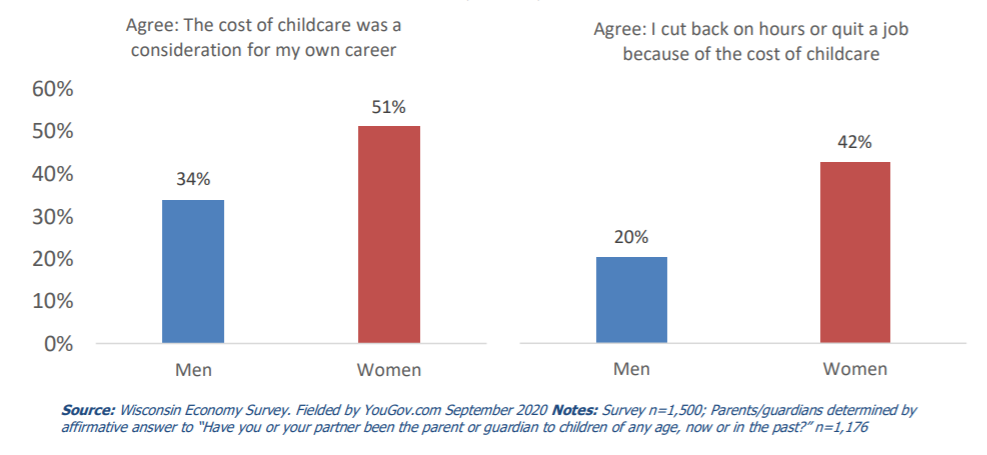

In the Midwest Too, Women’s Jobs & Careers Are More Often Impacted

Results from a September 2020 survey, led by the EDA University Center at the Division of Extension, also highlight how men and women are impacted differently by the lack of affordable childcare or quality childcare. Independent of COVID-19, among respondents who were the parents of children of any age (n=1,176), three times as many women than men, 30% as compared to 10%, reported that they have, at some point, cut back on hours or quit a job because of the quality of childcare that was available. As shown in Figure 2, 51% of women and 34% of men reported that the cost of childcare was a consideration in planning for their own careers. When narrowing the question, and asking if respondents, personally, cut back on hours or quit a job because of costs, 20% of men and 42% of women reported that they had, indeed, cut back on hours or quit a job because of childcare costs (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Role of Childcare Costs in Employment Decisions by Gender (n=1,176)

Source: Wisconsin Economy Survey. Fielded by YouGov.com September 2020 Notes: Survey n=1,500; Parents/guardians determined by affirmative answer to “Have you or your partner been the parent or guardian to children of any age, now or in the past?” n=1,176

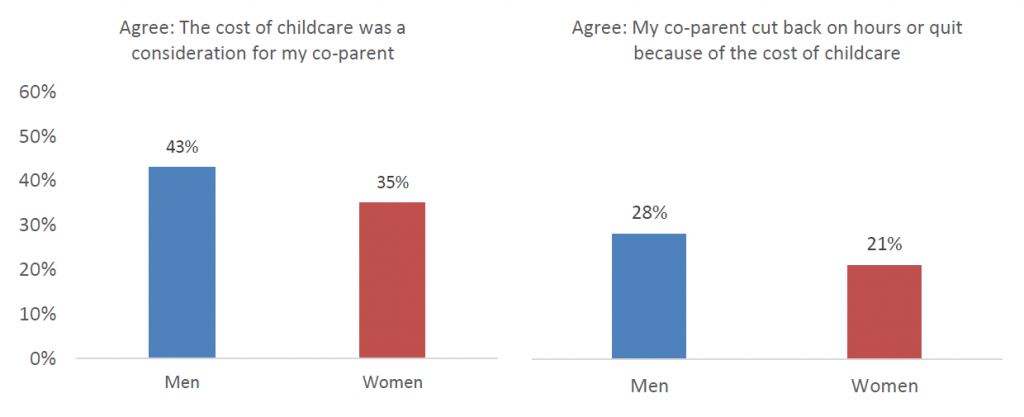

Different Perceptions for Different Genders?

When we look more closely at respondent perceptions of their spouse, partner or co-parent’s experience, something interesting emerges. We asked respondents to tell us about the toll that childcare had on their spouse, partner or co-parent’s career. Women’s perceptions of the toll on their (typically male) partners largely matches what men assess as the toll on themselves. Men’s perceptions of the toll on their (typically female) partners, however, are much lower than what women see as the toll on themselves. These results suggest that men underestimate the burden of childcare for women compared to how women see it for themselves. When we asked about the cost of childcare on career choices, 42% of women reported that they, themselves, cut back or quit because of cost (Figure 2). Yet only 28% percent of men reported that their spouse or partner cut back on hours or quit a job because of the cost of childcare (Figure 3), suggesting that men perceive a lesser impact of expensive care on their partner’s experience than their partners see for themselves.

Similarly, 51% of women reported that they, themselves, took childcare costs into consideration when planning their careers (Figure 2). Yet, only 43% of men reported that the cost of childcare was a consideration in career planning for their spouse, partner or co-parent (Figure 3). Thirty percent of women reported quality of childcare as a reason for cutting back or quitting. Yet, just 17% percent of men reporting said that their spouse, partner or co-parent cut back on hours or quit a job because of quality, close to half of what women reported for themselves.

Figure 3: Role of Childcare Costs in Employment Decision for Co-parent by Gender (n=1,176)

Source: Wisconsin Economy Survey. Fielded by YouGov.com September 2020 Notes: Survey n=1,500; Parents/guardians determined by affirmative answer to “Have you or your partner been the parent or guardian to children of any age, now or in the past?” n=1,176

Women’s assessment of the impact on their partners was more compatible with how men answered for themselves. Thirty-five percent of women reported that cost was a consideration in career planning for their spouse, partner or co-parent (Figure 3), which was roughly equal to the 34% of men who reported that they, themselves, considered childcare costs in career planning (Figure 2). In other words, women seem to accurately assess the toll of childcare costs on their partners. There is similar symmetry between women answering about their partners and men’s own answers when asked how childcare costs affected their decision to cut back on hours at 21% (Figure 3) and 20% (Figure 2), respectively. When asked about childcare quality, women actually overestimated the impact—17% of women reported quality as a reason their spouse, partner or co-parent cut back or quit, as compared to the 10% of men who reported quality as an actual reason for doing so.

These results highlight how childcare is a challenge for women and, perhaps, so is coming to a shared understanding of the challenge with their partners. Women are not only relinquishing income based on the cost and quality of available childcare, but the toll this is taking may not even be recognized by

their own spouses, partners or co-parents. In households where women prefer to work part- or fulltime, perhaps more of a shared perspective on childcare would help both women and men better balance children and work responsibilities in a way that preserves women’s labor market opportunities.

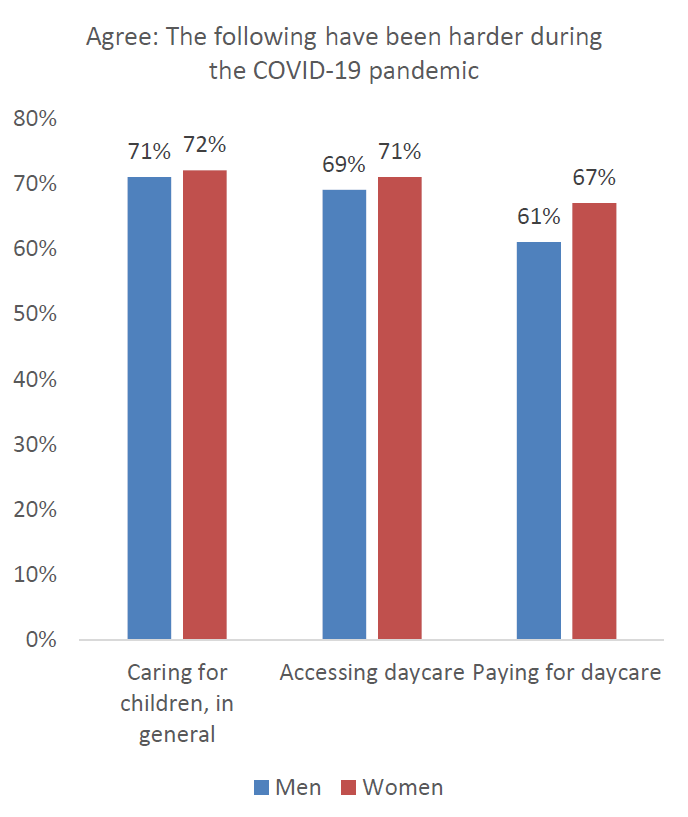

COVID-19 Increase Childcare Challenges

As part of the September 2020 survey, we asked parents about challenges they have been facing during the COVID-19 pandemic. There are no strong statistical differences in the proportion of men (71%) and women (72%) who agree that caring for children, in general, has been harder during the pandemic. Likewise, men (69%) and women (71%) report in relatively similar numbers that accessing childcare has been harder. However, more women (67%) than men (61%) report that paying for daycare has been more difficult during the COVID-19 pandemic. The concern may be that, when faced with difficulty in accessing and paying for childcare, women will leave the labor force in greater numbers than men.

Figure 4: COVID-19 Childcare Challenges by Gender

Source: Wisconsin Economy Survey. Fielded by YouGov.com September 2020

Short & Long-term Consequences

For women leaving the labor force during the COVID-19 pandemic, that means loss of pay. At the household level, it may mean lower income and less household spending which can ripple through an already struggling economy. For working mothers, it may also mean a loss of benefits such as healthcare. In

addition, potentially, these women lose their own and their employer’s contributions to retirement savings. They are also losing working years that would factor into their future social security benefits. So, the financial losses can echo well into the future.

If these women do eventually return to work, they will likely earn a lower salary or wage than before (Arulampalam 2013, Spivey 2005). It can be difficult to get back on the same earnings trajectory after a period of joblessness especially during a recession (Couch et al. 2011). The longer an individual is out of the labor force the harder it can be to re-enter and earn comparable wages (see Nichols et al. 2013 for discussion). The same can go for women who go part-time. Part-time work often comes with a pay penalty which can have similar long-term consequences for future earnings (Golden, 2020).

With these lasting wage consequences, the growing number of women leaving the labor force as a result of COVID-19 and childcare responsibilities may mean the trend towards a narrowing gender wage gap may stall or, in the extreme, even widen. So, it exacerbates part of the wage issue that created these circumstances for women in the first place.

Developing a Solution

There is potential, though, for a shift that benefits working parents but especially women. This could be the impetus for new childcare solutions which could help employees with children at home. Parents aren’t the only ones with something to gain from childcare solutions, however. As we recover, the ability to hire workers may be constrained by childcare. So, employers may be better positioned to acquire and retain the workers they need, simultaneously reducing search and training costs, if parents can secure affordable, reliable quality childcare. With their kids in childcare that they trust, workers may also have enhanced presenteeism, meaning they are more focused because they are not distracted by the stress and worry of their children’s care throughout the day. Communities can benefit too. As childcare is a setting for early childhood development, communities benefit from the availability of care well into the future via lower crime and more successful students, as examples (see Rolnick and Grunewald 2003 for a discussion).

Interestingly, the results from the Wisconsin Economic Survey suggest men and women are looking for solutions to childcare in different places. Respondents said that parents and childcare providers bear the greatest responsibility in finding solutions to childcare issues, with public and private schools bearing the least responsibility for our respondents. Men and women assign responsibility to the government to find solutions to childcare issues in different ways, with women assigning greater responsibility at all levels of government — local, state, federal government, elected officials — than men. Women, as opposed to men, assign greater responsibility to employers to help find childcare solutions.

For employers, work availability due to childcare may not be an issue now. Understandably, many businesses have more dire or more pressing concerns. That said, employers can play a role in relieving the childcare dilemma. Employer-led childcare co-operatives may offer a path forward. Even without explicitly getting into child care provision, expanding enrollment or benefit counseling for dependent care savings account benefits, switching to core-hour or flexible schedule models, or perhaps just offering facilities in the form of unused space can all contribute to mitigating the challenges for their employees.

Government at multiple levels have also taken some steps to aid childcare. The CARES act included extra funding for childcare providers by increasing Block Grant funding. But as with all spending associated with the CARES Act, these additional resources are temporary. Also, at the Federal level, the Paycheck Protection Program certainly offered much needed financial support to some providers. Yet many child care providers were likely ill-suited to benefit from the program. The Paycheck Protection Program is a fully forgivable loan as long as businesses retain their employees and spend 75% of the loan on payroll. While payroll is a significant expense for childcare providers, they also need support for cleaning and sanitation. Further, payroll expenses may have declined during the pandemic due to reduced capacity. There is also growing concern that banks, which administered the PPP program, prioritized service to those with existing relationships and larger organizations. If that’s the case, small or unbanked childcare providers would be disadvantaged in securing funds.

At the state-level, many states have pursued support strategies. In Wisconsin, the Department of Children and Families opened a second round of Child Care Counts in late October. The grants are set up in two categories: (1) to support compliance status, quality level, and enhancing health and safety

practices and (2) support the costs to recruit and retain high-quality employees.

References

Arulampalam, W. (2013). Is Unemployment Really Scarring? Effects of Unemployment Experiences on Wages. The Economic Journal, 111(475), F585–F606.

Bipartisan_Policy_Center. (2020). Nationwide Survey: Child Care in the Time of Coronavirus. Retrieved from https://bipartisanpolicy.org/blog/nationwide-survey-child-care-in-the-timeof-coronavirus/

Black, D. a., Kolesnikova, N., & Taylor, L. J. (2014). Why do so few women work in New York (and so many in Minneapolis)?? Labor supply of married women across US cities. Journal of Urban Economics, 79, 59–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2013.03.003

Bureau_of_Labor_Statistics. (2020). The Employment Situation-September 2020 [Press release]. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf

Chrisnacht, C. & Sullivan, B. (2020, May 8) The Choices Mothers Make. The United States Census Bureau. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2020/05/the-choicesworking-mothers-make.html.

Couch, K. A., Jolly, N. A., & Placzek, D. W. (2011). Earnings losses of displaced workers and the business cycle: An analysis with administrative data. Economics Letters, 111(1), 16–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2010.12.011

Golden, L. (2020, February 27). Part-time workers pay a big-time penalty. The Economic Policy Institute. Retrieved from https://www.epi.org/publication/part-time-pay-penalty/.

Graf, N., Brown, A., & Patten, E. (2019, March 22). The narrowing, but persistent, gender gap in pay. Pew Research Center. Washington, DC. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/facttank/2019/03/22/gender-pay-gap-facts/.

Gurley-Calvez, T., Biehl, A., & Harper, K. (2015). Time-Use Patterns and Women Entrepreneurs. The American Economic Review, 99(2), 139–144.

Jessen-Howard, S., & Workman, S. (2020). Coronavirus Pandemic Could Lead to Permanent Loss of Nearly 4.5 Million Childcare Slots. Early Childhood. Retrieved from https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/earlychildhood/news/2020/04/24/483817/coronavirus-pandemic-lead-permanent-loss-nearly-4-5-million-child-care-slots/

Nichols, A., Mitchell, J., & Lindner, S. (2013). Consequences of Long-Term Unemployment. The Urban Institute. Retrieved from https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/23921/412887-Consequences-ofLong-Term-Unemployment.PDF

Parker, K., & Wang, W. (2013). Modern Parenthood. Roles of Moms and Dads Converge as They Balance Work and Family. Pew Research Center Report. Washington, D.C.

Rolnick, A. J., & Grunewald, R. (2003). Early childhood development: Economic development with a high public return. Fedgazette, 15(2). Minneapolis: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Retrieved from https://www.minneapolisfed.org/article/2003/early-childhooddevelopment-economic-development-with-a-high-public-return

Runge, Kristin K. (2020). Wisconsin Economy Survey. Fielded by YouGov for the Division of Extension, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Spivey, C. (2005). Time off at what price? The effects of career interruptions on earnings. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 59(1), 119–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/001979390505900107