OVERVIEW

June 2022 — As a growing number of Wisconsin farms struggle to survive, many farm households (families) are dependent on off farm income to offset weak and unstable farm sourced income. Over the five-year average (2016-2020) average household income for Wisconsin farm operators is $98,353of which $20,210 comes from farming activities, and the remaining $78,143 comes from off farm sources. One strategy to ensure the continued operation of most Wisconsin farms is to focus on enhancing off farm employment opportunities.

KEY POINTS

- Nearly half (48.2%) of Wisconsin farms had sales less than $10,000 and only 7.3 percent had sales above $500,000.

- Slightly over half (53.1%) of farm operators reported farming was not their primary occupation and 58.1 percent worked off the farm.

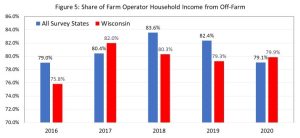

- From 2016 to 2020 the typical Wisconsin farm household received 75 percent of its income from off farm sources.

- From 2016 to 2020 the smallest farms, those with sales less than $100,000 (¾ of all Wisconsin farms), 102.2 percent of farm operator household income came from off farm sources.

Agriculture remains an important part of not only the Wisconsin economy but also the self-identity of the state. Widely known as the Dairy State Wisconsinites are proud to don their cheese-head hats while cheering on the Packers. In the latest analysis of the contribution of agriculture to the Wisconsin economy Deller (2019) found that on-farm operations support a total of 154,000 jobs and food processing, which is dominated by cheese production, supports 282,000 jobs. Combined agriculture accounts for 11.8 percent of total Wisconsin employment. But the Wisconsin farm economy has been undergoing significant changes over the past several decades. One of the largest drivers of these changes has been growth in production technologies that fostered economies of scale which in turn drove farms to grow, largely through consolidation. For example, in 1920 there were 180,295 farms in Wisconsin, by 1950 there were 168,561, by 1982 the number had declined to 82,199 and in 2017 Wisconsin had 64,793.Yet over the same period the amount of farm product soared through increases in productivity.

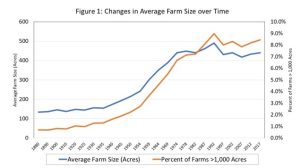

From a national perspective, the size of a typical farm, as measured by acreage, began to grow in the mid-1930s (Figure 1). Between 1880 and 1935 the typical farm in the United States was about 145 acres, but by 1992 that size had jumped to 491 acres. Prior to 1935, only about one percent of farms were greater than 1,000 acres, but again by 1992 almost one in ten farms (9%) was larger than 1,000 acres. These trends have been widely studied (e.g., Lin, Coffman, and Penn 1980; Kislev and Peterson 1982; Park and Deller 2021), and as noted by Gardener (2002), there appears to have been a clear slowdown in farm consolidation in the 1980s.

James MacDonald from the University of Maryland (2020) argues that these simple averages have masked persistent consolidation across agriculture. If one considers crop-land but excludes both farmlands not in productive use as well as grazing land, one can see farms operating at least 2,000 acres of cropland accounted for just 15 percent of all cropland in 1987, but that share had increased to 37 percent by 2017. The share of crops from very large farms (those with at least 10,000 cropland acres) increased fourfold from 294 in 1987 to 1,191 in 2017. Consider the case of dairy farming: in 1987, one percent of dairy farms had 500 or more milking cows, yet by 2017 that share had increased to 6.3 percent, and more importantly, those larger dairies now accounted for 56.4 percent of milk sales. The very largest dairies, those with more than 5,000 cows, accounted for 12.4 percent of total milk sales.

FIGURE 1: CHANGES IN AVERAGE FARM SIZE OVER TIME

In addition to the driving forces of economies of scale leading to fewer and larger farms, there has been a growing number of farmers that have elected to leave farming. The long tradition of subsequent generations taking over the family farm has weakened.Further, farmers are finding that the level of income that goes to support the farm household or family is becoming unsustainable. One simple measure of this is to track average farm earnings over time (Figure 2).Here farm earnings are defined as farm proprietor income, farm wages and salaries, and any supplements to farm wages and salaries and can be thought of as income going to the farmer and in turn the farm household or family. After adjusting for inflation (all figures are in 2020 dollars), the average annual per farm earnings from 1969 to 2020 is $23,971 which is below the national average of $30,570. If we limit the timeframe to 2010 to 2020, average earning per farm increased to $40,733 (still below the national farm average of $49,573).

FIGURE 2: FARM EARNING PER FARM PROPRIETORSHIP (IN 2020 DOLLARS)

Perhaps one of the struggles that farmers face in terms of providing income to the household or family is the inherent instability of farming. Consider the period from 2007 to 2020, where the average earnings per farm did increase, the severity of boom and bust seems to have elevated. While farmers have built this inherent instability into many of their business decisions, the ramifications on the financial health of the farm household has consequences. This instability, coupled with historically low rates of return (e.g., earnings), is a major driver of the breakdown of intergenerational transfers of farms. Many express a desire to continue with the family farm, but the fiscal stresses on the farm family is unattractive to future generations of farmers.

In this WIndicator we explore how the changing structure of Wisconsin farming has altered the economic relationship between farming and rural communities.Historically people have thought of rural communities being dependent upon farming activities and the contribution of farming to the economic health of those communities. Wisconsin farming, however, has changed over the past several decades and is causing many to rethink that historical perspective. Using both USDA Census of Agriculture and Agricultural Resource Management Survey (ARMS) data we find that farm households (families) are increasingly dependent on income from off the farm.The policy implications are clear: to ensure the continued viability of most Wisconsin farms greater attention must be given to off farm employment opportunities.

CHANGING STRUCTURE OF WISCONSIN FARMS

Many farmers, particularly after the rash of farm bankruptcies in 2017 and 2018, decided that the status quo is unsustainable and fundamental decisions about the operations of the farm had to be addressed. Some elected to follow the controversial advance of former Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue (World Dairy Expo, Madison, Wisconsin October 2019): “In America, the big get bigger and the small go out. I don’t think in America, for any small business, we have a guaranteed income or guaranteed profitability…”. But many Wisconsin farmers pushed back against this idea and pursued other strategies.

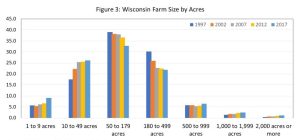

Using farm acreage as our measure of size, we have seen growth in the number of smallest farms as well as more modest growth in the number of largest farms. In 1997, 23.2 percent of Wisconsin farms operated less than 50 acres, but by 2017 that share of small farms increased to 35.3 percent of all farms. The largest farms, those with 1,000 or more acres, increased from 1.9 percent to 3.6 percent of all Wisconsin farms. The number of farms, in percentage terms, that could be considered “average size” (the “50 to 179” and “180 to 499” acres taken together) declined from 1997 to 2017.What we have been experiencing in Wisconsin is a “hollowing out” of the middle of farm distribution by size: we are seeing growth in the smallest and largest farms and decline in the “average size” farms.

FIGURE 3: WISCONSIN FARM SIZE BY ACRES

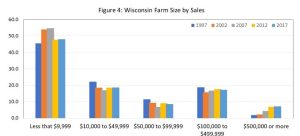

There are limitations to using acres as farm size given the Wisconsin farming economy.Acres is an appropriate measure for most crop farms (e.g., corn, soybeans, wheat, etc.) but is likely inappropriate for livestock and specialty crops such as fruits and vegetables. For example, some large dairy CAFO operations are located on relatively small farms as measured by acres. An alternative measure of farm size is to group farms by sales or revenues (Figure 4). Unlike the acreage measures, the shift in farm sizes with revenue is more subtle. While average farm sales increased from $85,056 in 1997 to $176,368 in 2017, the distribution across different farm sizes has remained relatively stable. Only the percent of farms with sales over $500,000 increased going from 1.9 percent in 1997 to 7.3 percent in 2017.

FIGURE 4: WISCONSIN FARM SIZE BY SALES

Perhaps more fundamental to the discussion of farm structure in Wisconsin is the large share of farms that have modest sales. In 2017 48.2 percent of all farms included in the Census of Agriculture reported sales of less than $10,000, and 32 percent had sales of less than $2,500. While the distribution of farms across the sales spectrum has remained relatively stable, the large number of farms with limited sales raises a fundamental question about the definition of a farm. Is a farm with sales less than $10,000 a truly viable farm or is it more of a secondary activity type enterprise?

To shed light on this challenging question, Hoppe, Perry, and Banker (2000) offer alternative classifications of farms in a study of the American Heartland (western Ohio to northern Missouri and southern Minnesota, Wisconsin is not included in this study). They break what they refer to as “small family farms”, those with sales less than $250,000, which account for 92 percent of farms in the study area, into five different categories including retirement and residential/lifestyle farms. They find that nearly one in ten farms are classified as retirement whereas nearly two in five farms are residential/lifestyle farms. These latter farms are defined as small (sales less than $250,000) whose operators report a major occupation other than farming.Looking more closely at Wisconsin farmers, in 1997 54.5 percent reported farming as their primary occupation and 46 percent did not work off the farm, but by 2017 46.3 percent of farmers reported farming as their primary occupation and 41.9 percent did not work off the farm.

While there is no clear answer to what defines a viable farm enterprise, it points to a trend of farmers electing to remain in farming but at a reduced scale. Farmers seldom have any influence over the prices they receive for their products (they can implement strategies to minimize the impact of fluctuations in prices such as crop insurance) but they do have control over the costs of their operations. Here some farmers face the viable option of reducing their scale of operations to reduce costs. Some dairy farmers have elected to move from dairy into beef production in order to maintain the farm operation but at reduced costs and labor time. Other dairy farmers are reducing cow herd size and adopting a grazing approach. Crop farmers may elect to reduce the size of planting and harvesting and rent out part of their land to other farmers. Here the farmer is able to remain in farming but with less risk exposure.

Alternatively, some farmers may elect to move from “commodity” to “product” production to take advantage of growth in local foods markets.The difference here being that “commodity” (for example, yellow corn number two) production flows into the larger food stream where farmers are largely price takers. The movement to “product” production, such as organic sweet corn, allows the farmer to add value to pricing by marketing to targeted audiences, such as local food systems. The scale of operation could be smaller to reduce costs, but it allows the farmer to maintain the farm.

A third factor that is at play is the ability of new farmers to enter farming at scale. Many new enterprises require significant startup capital, and this is particularly true for farming which can be “capital intensive” whether it is land, buildings, equipment or livestock. Estimates for the required capital to start a farm varies widely depending on the commodities being produced to land prices, among other factors. It is not uncommon for capital investments of seven figures to be discussed. Unless there is a generational transfer of farm assets the ability of new farmers entering agriculture these startup costs are prohibiting. The strategy is to start small and grow the farm over time. Thus, it is possible for what Hoppe, Perry, and Banker (2000) refer to as residential/lifestyle farms are new farms that are in the early stages of operation. But are these early-stage farms able to generate sufficient revenues to support the farm household or family or is off farm income required?

In summary, we are seeing a “hollowing out” of the distribution of farming in Wisconsin with modest growth in the largest farms and higher growth in the smaller farms.The growth in the smaller farms comes from at least four sources: downsizing in a transition to retirement, downsizing to reduce costs of the farm but maintain operations (perhaps becoming residential/lifestyle farms), new startups with long-term plans to grow, and specialty farms that are targeting smaller markets including local food systems. The question is the role of off farm income in allowing these smaller farms to remain in operation.

OFF FARM INCOME

To explore the degree to which Wisconsin farmers rely on off farm income, we use the Agricultural Resource Management Survey (ARMS) from the U.S. Department of Agriculture which is USDA’s primary source of information on the production practices, resource use, and economic well-being of America’s farms and ranches. The ARMS survey sample is designed to provide coverage of all farms in the 48 contiguous States plus state level data for 15 major cash receipts states. The farm population includes all establishments which produced and sold, or would normally have sold, at least $1,000 of agricultural products during the previous year. Because Wisconsin is among the 15 major cash receipts states, detailed summary data from the ARMS is available. The data are available annually from 2016 to 2020 thus providing five years of Wisconsin specific data. For brevity, we will report the averages over those five years in our analysis of off farm income.

The five-year average household income for Wisconsin farm operators is $98,353, which is about 108 percent of the national average household income, of which $20,210 comes from farming activities, and the remaining $78,143 comes from off farm sources. The corresponding national averages are $117,475 for total farm operator household income, of which $22,466 comes from farm operations and $95,009 comes from off farm sources. While there are some annual fluctuations across the five years, the share of farm operator household income from off the farm is consistently above 75 percent (Figure 5). Sources of off farm income include in dividends, interest and rental payments not associated with the farm, wages and salaries associated with non-farm employment, and transfers to individuals such as social security payments. The dominate source of off farm income is associated with off farm employment as opposed to transfer payments such as social security or dividends and interest income. Note that the magnitude of farm household income coming from farming activities estimated in the ARMS data is comparable to the farm earnings estimates reported in Figure 2.

FIGURE 5: SHARE OF FARM OPERATOR HOUSEHOLD INCOME FROM OFF-FARM

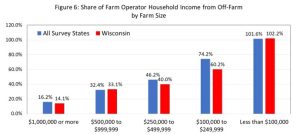

If we group farms by size, here size is based on farm revenues or sales, our understanding of the level of farm operator household income from off farm sources becomes clearer (Figure 6). As expected, larger farms tend to be less dependent upon off farm income as larger farms have greater capacity to generate revenues and income to the farm household than smaller farms. The largest farms, those with over $1,000,000 in sales, are still drawing off farm income into the farm household: for Wisconsin 14.1 percent and 16.2 percent for all states within the ARMS database. Any additional income is supplemental to the farm derived income. It should be noted that the level of household income for these largest farms is substantial at a five-year average (2016-2020) of $345,755 of which $297,175 comes from farming activities.

FIGURE 6: SHARE OF FARM OPERATOR HOUSEHOLD INCOME FROM OFF-FARM BY FARM SIZE

For the smallest farms, those with sales less than $100,000, which based on the 2017 Census of Agriculture accounts for three quarters of all Wisconsin farms, off farm income accounts for 102.2 percent of farm operator household income. Off farm sourced income accounting for more than 100 percent of farm household income is attributed to the farms operating at a net loss. Over the five years of the ARMS data the typical Wisconsin farm in this sales category cost the farm household -$1,855 whereas the average off farm income was $86,395. At this level of combined on and off farm income, farm households in this classification of farm size is at about 92.7 percent of U.S. average household income. One could argue that these farms are most in line with what Hoppe, Perry, and Banker (2000) refer to as residential/lifestyle farms.

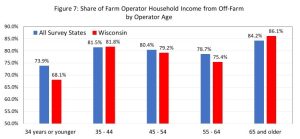

To complete our analysis, we also grouped farms by the age of the farm operator (Figure 7). For the four classifications of farmers over age 35 the level of dependency on off farm income ranges from 75.4 percent (age 55-64) to 86.1 percent (age 65 and older), most of which are close to the U.S. average (or all states within the ARMS database). The youngest group (age 34 or younger) had the lowest dependency of off farm income at 68.1 percent. This suggests that those beginning farmers that are starting small and require off farm income to support the household may not as common as thought. These data, however, cannot separate those younger farmers that have taken over the family farm and those that are starting a new farm from the ground floor. Unlike the clear pattern across farm size, the differences across farm operator ages seems less meaningful.

FIGURE 7: SHARE OF FARM OPERATOR HOUSEHOLD INCOME FROM OFF-FARM BY OPERATOR AGE

IMPLICATIONS

Other than the very largest farms, off farm income to the farm operator’s household has become vital to the economic survival of the household or farm family. This is particularly true for the smaller farms which dominate the Wisconsin farming landscape. Returning to former Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue’s general advice to farmers to “get big or get out”, Wisconsin farmers have chosen an alternative path.The realization that what had historically been the “average size farm” is largely unsustainable has seen many farmers elect to not “get bigger” but rather seek a third option. Many farmers simply do not want to “get big” (option one) nor do they want to “get out” or close the farm operation (option two).The third option may be to reduce the scale of operations to reduce costs but to maintain a functioning farm.This could be shifting from dairy to beef or downsizing the herd and moving to grazing, or even electing to rent out some land to neighboring farmers and operate on a smaller scale.Many farmers are electing to grow alternative crops but at a smaller scale and perhaps sell into local food systems.Here the transition maybe slow movement into retirement or into what could be described as residential/lifestyle farms.

A key to this downsizing option is off farm income to ensure a financially stable farm household or family. Based on the ARMS data for Wisconsin the level of dependency of off farm income is high regardless of the scale of farm operation. For all but the largest farms, farm household income is predominantly dependent on off farm sources. Indeed, for the smallest farms (less than $100,000 in sales which represents about 75 percent of all Wisconsin farms) farm household supplement farm operations. In other words, these small farms tend to operate at a loss and income from off the farm is used to make the farm financially whole. Because there is significant levels of off farm income coming into the farm household, the farm can remain in operation.

This last point cannot be over emphasized: without significant off farm income most Wisconsin farms would be unable to sustain the farm household. The policy implication is clear: in order to maintain all but the largest farms, there must be viable employment opportunities in local communities. Without these employment opportunities the farms become financially unsustainable. The relationship between agriculture (farming) and local communities has historically been viewed as one directional: as farms do better economically the better local communities perform economically. In other words, vibrant rural communities are dependent upon vibrant farms. The growing dependency of off farm income to maintain the farm household, and in turn the farm itself, this directional relationship has flipped: in order to maintain viable farms, there must be employment opportunities in those local communities. If the rural communities within commuting distance to the farm are struggling to provide viable employment opportunities, the future of the farm is at risk.

This WIndicator benefited from the comments of Zach Raff (UW-Stout) and Jeremy Beach (UW-Madison) and all errors and interpretations of the analysis are the responsibility of the author.

References

Deller, S.C., 2019. Contribution of Agriculture to the Wisconsin Economy: An Update for 2017. Center for Community and Economic Development, Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Gardner, B.L., 2002. American Agriculture in the Twentieth Century: How it Flourished and What it Cost. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Hoppe, R.A., J.E. Perry, and D. Banker., 2000. ERS Farm Typology for a Diverse Agricultural Sector. Agricultural Information Bulletin Number 759. USDA ERS

Kislev, Y. and W. Peterson. 1982. “Prices, Technology, and Farm Size.” Journal of Political Economy. 90 (3): 578–595.

Lin, W., G. Coffman and J.B. Penn, 1980. US Farm Numbers, Sizes and Related Structural Dimensions. US Government Printing Office.

MacDonald, J.M., 2020. “Tracking the Consolidation of US Agriculture.” Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy. 42 (3): 361–379.

Park, S. and S.C. Deller. 2021. “Effect of Farm Structure on Rural Community Well-Beling.” Journal of Rural Studies. 87: 300-313.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by a grant from the United States Department of Commerce Economic Development Administration in support of Economic Development Authority University Center (Award No. ED16CHI3030030 and ED21 CHI3030029). Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Department of Commerce Economic Development Administration.