Volume 5, November 2022

Overview

Key Points

- BIPOC-owned and immigrant-owned businesses have a large and growing presence in Wisconsin.

- There is little evidence-based information on the specific needs of these businesses.

- Entrepreneurs of color described specific needs for financial, human, and social capital development.

- It is essential for entrepreneurial support programs to recognize how these capitals are interconnected and take a systems approach to service and support.

November 2022 — People of color are starting and growing businesses at high rates in Wisconsin. This study explored the experiences of BIPOC entrepreneurs in Fond du Lac County through 1-1 interviews and the Community Capitals Framework (CCF). Business owners expressed satisfaction with the natural beauty and safety of the area while describing limited technical knowledge (human capital), networks (social capital), and financial capital in the critical startup phase of their entrepreneurship. Business development technicians and educators can use this study to better support entrepreneurs of color in their Wisconsin communities.

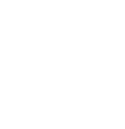

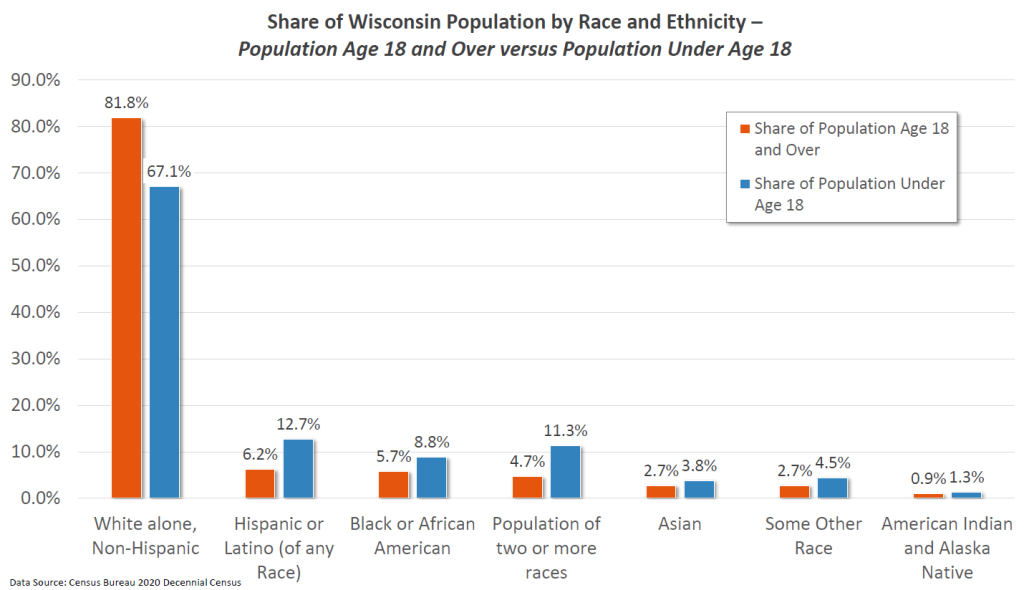

Wisconsin is becoming increasingly diverse as the state is now home to large and growing populations of Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) as well as immigrants (see figure 2). This diversity presents an economic opportunity as BIPOC and immigrant residents in the U.S. start and grow businesses at higher rates than the native population (Fairlie & Robb, 2010). However, there is little research on the specific needs and support necessary for these business owners to start and grow their businesses. A good example of this trend is semi-rural Fond du Lac County in northeastern Wisconsin where a growing number of BIPOC (See Figure 2) and immigrants are living, working, and starting businesses.

In 2014, local economic development organizations began collaborating more intentionally, forming an Entrepreneurial Development System (Lichtenstein & Lyons, 2001) to complement rather than duplicate services and better foster a culture of entrepreneurship. It became apparent through this process that business support efforts were missing entrepreneurs of color, and little information existed on the services that entrepreneurs of color would value.

To learn more, Extension partnered with Ripon College interns to interview 35 African-American, Asian, Latinx, Native American, and immigrant business owners in 2014-2015. Taking an asset-based approach, Extension used the Community Capitals Framework (Flora et al., 2016) to analyze the interviews and understand how to better support business success among BIPOC entrepreneurs in predominantly white areas.

Community Capitals Framework (CCF)

CCF describes eight different types of capital that together drive community well-being: natural capital, cultural capital, human capital, social capital, political capital, financial capital, and built capital. Social capital is further described by it’s two facets: bridging social capital – connecting with others who are different – and bonding social capital – connecting with others who are similar (see figure 3).

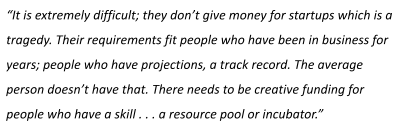

Financial Capital: Access to Funding

Most business owners in this study indicated they lacked adequate financing at startup. Even so, only 15 of the 35 applied for loans from formal lenders like banks. Some who chose not to apply felt certain they would be denied due to their credit history or immigration status. Preemptively removing themselves from the loan application pool in this way is a phenomenon called credit self-rationing (Bates & Robb, 2016), since they may have been approved but didn’t find out for certain. Instead, business owners built up their own savings and/or borrowed from family. In these results we see that the entrepreneurs grew their financial capital by using both their human capital as they worked other jobs to save, and their bonding social capital, as they borrowed from family and friends who trusted them to start their businesses.

Working through formal lending channels, as white entrepreneurs often do, requires financial capital (such as savings or good credit), social capital (such as a relationship with an individual business lender), or political capital (such as being on the board of a credit union). Instead, they used the capitals they had more easily available to compensate and meet their goal.

Human Capital: Access to Information

Most business owners in this study felt they could have used more information at startup. They also preferred assistance in their own cultural context and language. For example, two Chinese immigrant business owners hired Mandarin-speaking business development experts in another state to help them get launched. This service would have been free locally. This demonstrates their choice to use bonding social capital with compatriots and financial capital as a way to get the information they needed rather than bridging social capital with the local business development experts. Similarly, a European immigrant business owner explained, “[I go to my] relatives in Illinois. They are in the restaurant business for longer…. I refer to them every time I had a question. They are successful business people.”

While a traditional source of business information and referrals for white business owners is often a chamber of commerce, 28 of the 35 participants in this study did not belong to a chamber or any similar peer group. For business owners with limited resources, participation in community and business organizations must be weighed against anticipated benefits accrued from participation. An African American entrepreneur described his decision this way: “I don’t intend to belong…until they can prove that they do something other than take your money. I think they’re a useless organization right now. [Tell me] what are you going to do? [What I’d like is that they] partner people together at a networking event – make sure [the new business] is able to make money. Have an interview like this and set them up with five other members who could use your service.” The bridging social capital required to join a majority white business organization did not feel worth the effort.

Social Capital: Networks and Inclusion

Even though participating entrepreneurs were not connected with formal business development organizations, they overwhelmingly reported feeling at home in the region and have plans to expand their businesses there. They said they started their businesses here because they live here, have family and friends here, and/or like the area. Participants are also active in community events like sports tournaments, festivals, religious activities, and nonprofit fundraisers through their businesses.

This shows strong cultural capital (culturally specific event participation), religious capital, and bonding social capital with people who were similar in interests, nationality, race, or religion. Research (Greve & Salaff, 2003) shows however, that the most successful entrepreneurs are able to utilize both bonding and bridging social capital to meet business goals by benefiting from high trust that comes from bonding interactions and new information that comes from bridging interactions.

Discussion

The entrepreneurs in this study demonstrated how access to some capitals can be leveraged to compensate for a lack of the others. The chances of business longevity and overall positive outcomes, however, are diminished when business owners don’t have the optimal combination. The role of racism and perceived or actual discrimination is also important to note and study further.

While most participants said they would have benefitted from more information, they also did not belong to or participate in the majority white local business development organizations or groups which could have provided such information. Participants said time, language, cost, and value were reasons they chose not to join. They also seemed to have a strong preference for bonding social capital interactions, which is consistent with Ruef, Aldrich, & Carter’s (2003) findings for BIPOC entrepreneurs at startup. Similarly, they seemed to lack bridging social capital to find the information they needed locally from people who are different but informed. Even though there were 11 white-led business development organizations available, their expertise and support programs did not reach or benefit these business owners.

In spite of this major gap, the participants felt positively about the natural capital (parks, lakes) and built capital (roads, buildings, parking) near their homes and businesses. In addition to their personal safety and good schools (social capital), these all play a role in increasing the satisfaction of the business owners’ and their families’ lived experiences. This allows them to contribute to the area’s financial capital and cultural capital more successfully and sustainably.

Recommendations

The experiences of business owners interviewed in this study indicate some changes that business development practitioners could make to enhance BIPOC and immigrant business startup experiences. As a starting point, professionals could begin by building trusting relationships with BIPOC entrepreneurs to understand their individual priorities. Taking this initiative via their professional status would start growing the bridging social capital of the development staff person and the entrepreneurs. The information learned through these relationships could be used to design programs with these specific business clients in mind which would be more effective than programs which work in other places or with different groups of entrepreneurs.

It is evident from this study that BIPOC- and immigrant-owned businesses are contributing to economic development locally but are not represented in key business organizations such as Chambers, lenders, or other supporting institutions. Inviting them into leadership positions to co-create activities and programming would also build bridging social capital for all participants. Increased bridging social capital from these opportunities would then lead to increased timely information, increased access to financial opportunities, markets, and clients for all business owners, and increased entrepreneurship in the community overall.

CCF is a helpful tool for recognizing the variety of capitals needed for business success. Providing access to one, such as financial capital, without regard to the others such as bridging social capital (introductions to community leaders) or political capital (invitations to participate in business development committees), etc. leaves a business owner ineffectively prepared to start and grow their business. Similarly, having access to startup funding (financial capital), networking (social capital), and technical assistance (human capital) is meaningless if the entrepreneurs’ family feels unsafe (social capital) or unstable due to the living conditions (built capital) in the community. Attending to all aspects of entrepreneurship, and the specific context in which BIPOC business owners experience them, is critical to maximizing business success among BIPOC and immigrant entrepreneurs in Wisconsin communities.

Special Features on Black, Latino, Asian, and Native Owned Businesses in Wisconsin

Special Features on Black, Latino, Asian, and Native Owned Businesses in Wisconsin How Ready are Owners for Business Succession and Transition?

How Ready are Owners for Business Succession and Transition? 2024 Wisconsin Connecting Entrepreneurial Communities Conference

2024 Wisconsin Connecting Entrepreneurial Communities Conference Business Owners of Color in Wisconsin: Trends & Outcomes

Business Owners of Color in Wisconsin: Trends & Outcomes