Volume 7, January 2025

Key Points

- Wisconsin is at the center of a national prosperity hotspot, but where prosperity is concentrated in the state and the drivers of prosperity have shifted over time.

- Prosperity is a dynamic process that changes over time; it is not a static state.

- There are hundreds of pathways to prosperity, suggesting the need for a nuanced, place-specific interpretation of what makes somewhere a good place to live.

- Prosperity is not restricted by metro status: rural places routinely have some of the highest place prosperity scores.

Introduction

What makes somewhere a good place to live?

Notions of community livability and quality of life have moved to the forefront of community discussions. Instead of focusing solely on economic growth, however, communities are increasingly turning their attention to a more holistic understanding of community well-being that includes a range of non-economic factors. Rather than pursuing growth for growth’s sake (more people, more jobs), communities are asking critical questions about what motivates people to want to live, work, start a business, or raise their family in a particular place.

In this WIndicator we focus on a relatively simple measure of prosperity to gain insight on the broader question of livability and contribute to ongoing local discussions. We explored patterns of place prosperity across four distinct dimensions: poverty, unemployment, housing, and education. Our analysis includes all U.S. counties and extends over time across three decades.

We find Wisconsin is at the center of the largest concentration of community-level prosperity in the United States, routinely faring better than the national average on all four dimensions we use to measure place prosperity. Though Wisconsin counties are doing well, keeping with a historical trend of above-average prosperity, the most prosperous places in the state have shifted over time and the factors that underlie prosperity have also changed. These findings are consistent with national trends showing that the ways in which prosperity evolves over time are incredibly diverse and complex.

The task of assessing community livability across different places has concerned researchers and community development professionals alike for decades. The challenge is that people value different community characteristics. For example, some prefer amenities that are often associated with more urban settings such as coffee shops, brew pubs, or live music venues while others prefer outdoor recreational opportunities that many rural settings offer. This task defining and measuring livability is growing more urgent as communities increasingly prioritize multi-dimensional measures of well-being that include both the economic and noneconomic factors that contribute to making somewhere a good place to live.

Despite widespread interest, research that can facilitate community discussions and form policy interventions is still in the early stages. Much of the difficulty in this area of research lies in a lack of clarity around prosperity itself: what does it really mean for a place to be “doing well,” and how can that well-being be measured and compared between places? What makes a college town “prosper” is surely different from a tech-hub, ski destination, or major city. The challenge is how to identify and meaningfully compare the prosperity of these unique places.

For a long time, economists have worked around these challenges by using “growth” indicators to measure prosperity. The logic goes that the best places have a growing number of businesses and jobs. The problem with this framing is that it does not universally align with the lived experience of “prosperous” places. Despite not having a growing population or accelerating economy, some places are still understood by-and-large to be good places to live, work, and raise families. Some communities are even reluctant to pursue traditional goals of economic growth (i.e., more jobs, more businesses, more housing, etc.) out of concern that such growth will alter the character of their community. Thus, a one-dimensional approach to place prosperity that only considers economic or demographic growth has the potential to ignore the more holistic ways places prosper. This is especially relevant for rural places by producing a misleading rhetoric of rural underperformance and inaccurately painting small, stable communities as “left behind.” To address these concerns, an effective measure of place prosperity must extend beyond the number of new jobs created or the number of new homes built, while maintaining the integrity of place individuality and dynamism.

Measuring Prosperity

One simple method that has been used to measure prosperity is to identify the counties that perform better than the national average across four dimensions: education, housing, poverty, and unemployment.1 To measure prosperity in this method, places are given a prosperity “score” from 0 (lowest) to 4 (highest). The highest scoring counties perform better than the national average across all four dimensions of prosperity, while the lowest scoring counties perform worse than the national average across all four dimensions. The intuition is that places with populations that are more educated, with better quality housing, lower poverty rates, and lower unemployment rates are generally the most “prosperous” places.

We build on this index by extending it across three decades, allowing us to consider prosperity as a process over time with places moving in and out of more or less prosperous states. These patterns of change in prosperity or what we call “prosperity pathways” can then be used to categorize places based on how prosperity has changed over time going back three decades. The categories are as follows:

Extremely Prosperous: Counties that are consistently above average across all dimensions.

Very Prosperous: Counties that are often above the national average across multiple dimensions.

Moderately Prosperous: Counties that are above the national average in some dimensions but are below the national average in other dimensions.

Slightly Prosperous: Counties that are often below the national average across multiple dimensions.

Lacking Measurable Prosperity: Counties that are consistently below average across most or all dimensions.

Our findings show that prosperity evolves over time in hundreds of different ways, varies across the urban-rural continuum, and is concentrated in different places across the United States. This approach helps reshape research and policy discussions away from wondering why rural places seemed to be always falling behind to instead asking how to effectively measure their successes.

National Context

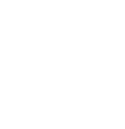

There is clear evidence that prosperity is regionally patterned across the U.S. Much of the region historically associated with the Rust Belt through the northern portions of the Great Plains is associated with greater prosperity by our measure. Wisconsin is within this spatial clustering of prosperous communities.

There are three larger geographic clusters of counties that can be characterized as less prosperous: much of the Deep South including parts of eastern Kentucky, parts of West Virginia, and much of western Tennessee; some of the Southwest including much of New Mexico and eastern Arizona; and a broad swath of the Pacific coast. There are also smaller geographic pockets of low prosperity such as the southern tip of Texas, parts of southern Florida, and parts of northeastern Michigan.

There are, however, outliers of this broad-strokes regional interpretation. For example, a common pattern in the Upper Midwest is prosperous suburban counties surrounding a less prosperous urban core, such as in Chicago (Cook County, Illinois) or Milwaukee (Milwaukee County, Wisconsin). The existence of these “outlier” places again affirms the need for a more nuanced view of place prosperity, one that takes seriously both regional relevance and unique place characteristics.

Also evident from this approach is the relevance of historical legacy on prosperity. This is particularly apparent for places where prosperity has stayed the same throughout the study period. For example, places that have been historically disadvantaged tend to show continued, and consistent patterns of lower levels of prosperity. High levels of prosperity also appear to be an enduring state. 192 counties never deviate from scoring above the national average across all dimensions.

This is not to say that prosperity is stagnant. In fact, for a vast majority of counties (87%), prosperity has changed over just the last three decades, sometimes by a great deal. While we can’t be certain of what drives change, there are evident patterns. Counties that have experienced the most change in prosperity over the study period often neighbor growing urban places or high-amenity rural places. Other counties that have experienced significant change appear to have had a unique economic or social “shock,” a major event that may have stimulated change. More research is required to discern the drivers of prosperity change and identify implications for community development.

Prosperity in Wisconsin Using this approach, there are several relevant findings with implications for Wisconsin.

- Wisconsin is at the center of a national prosperity hotspot

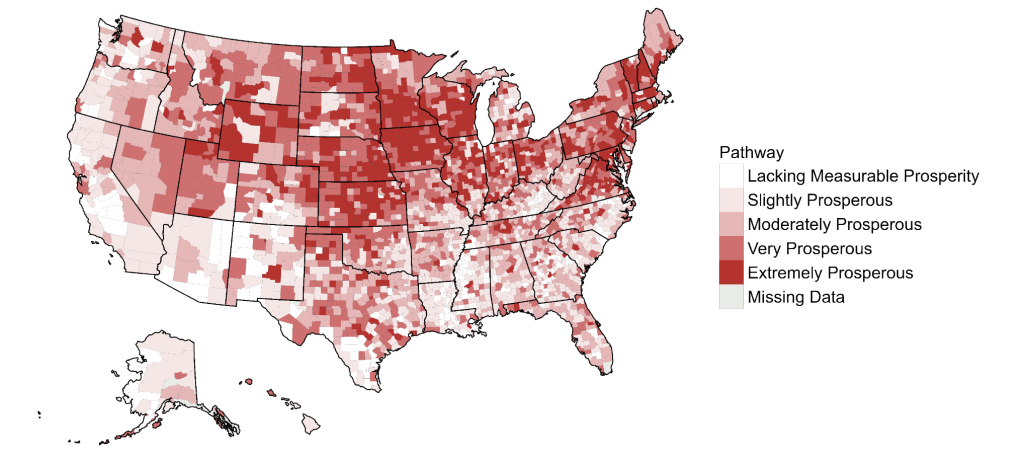

Wisconsin is at the center of the largest concentration of prosperity in the United States, routinely faring better than the national average on dimensions of poverty, unemployment, housing, and education. Eighteen Wisconsin counties have always scored better than the national average across all four dimensions. No counties fall into the lowest typology category, “lacking measurable prosperity.”

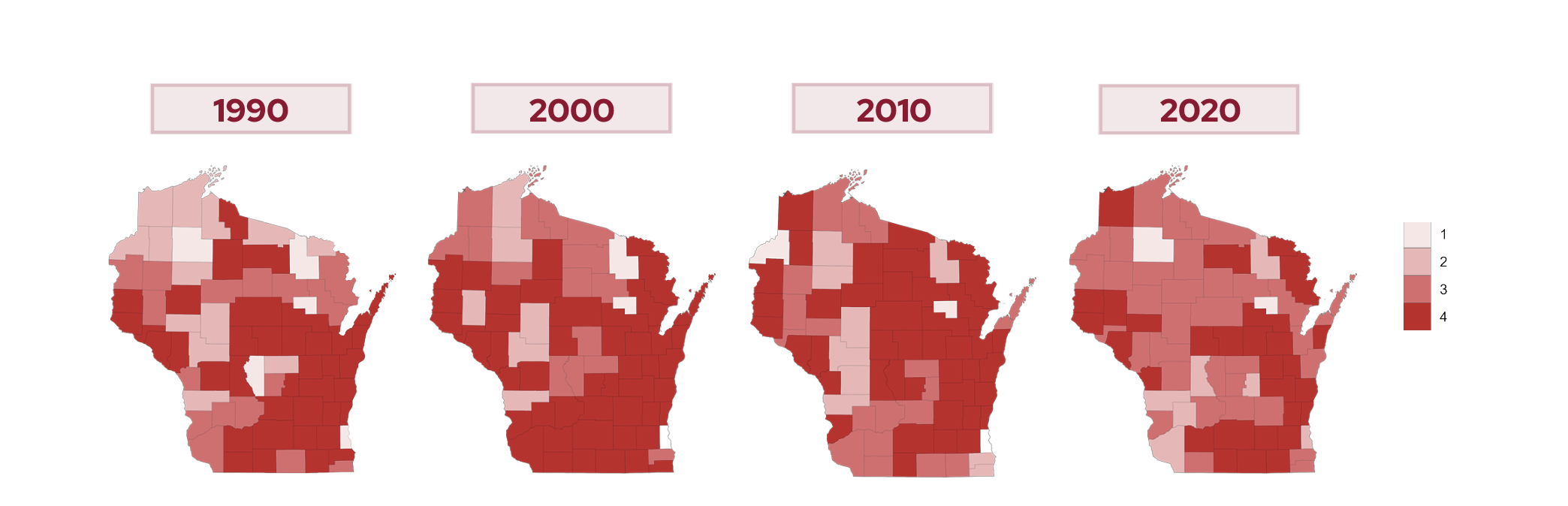

- Over time, prosperity in Wisconsin has shifted around the state

Where prosperity is concentrated in the state has changed over time. Though 2000 was Wisconsin’s “most prosperous” year (with 48 of 72 counties scoring a “4”), prosperity was concentrated in the southern and eastern parts of the state. Northern Wisconsin measured lower on the prosperity index. By 2010, however, this pattern shifted. More northern Wisconsin counties scored at the highest prosperity level, and in general, high-scoring prosperity shifted north and east. This shift is primarily driven by change in relative unemployment and poverty rates, though a variety of factors are likely at play in driving geographic prosperity change.

Compared to the national average, Wisconsin lost ground in the 2010s. This decline stems mostly from the education dimension of the prosperity measure. Keep in mind, however, that this captures only declines relative to the national average. In other words, education outcomes could be improving in Wisconsin over time, but still fall below the national average if the country as a whole improves even more. In other words, positive trends in Wisconsin are not keeping pace with larger national trends.

- Wisconsin’s drivers of prosperity have changed

The four dimensions that make up the prosperity index offer insights into how the drivers of Wisconsin prosperity have changed over time. In 1990, 67 percent of Wisconsin counties had a poverty rate better than the national average. This dramatically improved to 89 percent of Wisconsin counties over just ten years. A similar pattern is true for unemployment. In the final study period, all but three Wisconsin counties scored better than the national average for the unemployment rate. While this may not indicate a “real” reduction in poverty or unemployment, this demonstrates that Wisconsin is performing better than the rest of the nation in poverty and unemployment indicators.

Wisconsin has consistently outperformed the nation for housing quality and relative expense. In fact, the final study period shows all but one Wisconsin county scores better than the national average for the housing indicator, which includes substandard conditions and costs as a percent of household income. While people across Wisconsin have raised concerns about the cost of housing, relative to many other parts of the U.S., such as the West Coast, the cost of housing in Wisconsin is relatively reasonable. This is an encouraging finding that can be leveraged for further community development initiatives.

Of concern, however, is the change in how Wisconsin compares to the national high school dropout rate – a key indicator of educational attainment. In 1990, 93 percent of counties scored better than the national average high school dropout rate, meaning more Wisconsin teenagers graduated high school compared to the rest of the nation. Wisconsin has since fallen behind on this indicator. Now, less than half of Wisconsin counties score better than the national average. This is the primary driver for declining prosperity between 2010 and 2020 and suggests a clear need to consider education as a key opportunity to improve community well-being.

Policy Implications

Based on these findings, what should community development professionals do?

- Leverage existing assets

Every community is unique and offers their own blend of assets that promote prosperity. Communities should keep in mind what already drives prosperity in their community and explore new ways to leverage these assets, especially over time. For example, a consistent finding of our study is that Wisconsin excels in housing, especially when compared to the rest of the nation. This is not to conclude that the housing concerns many Wisconsin communities are struggling with should be discounted, but within a national context Wisconsin’s housing situation is better than many other places. These successes can be highlighted when continuing to foster community development and local prosperity.

- Assess prosperity over time

To get a more informative picture of prosperity, community economic development practitioners and policy makers should consider prosperity over time. Rather than focus on immediate changes, looking for trends and patterns might indicate what is to come. For example, understanding how Wisconsin education has fared over thirty years, rather than any one year taken by itself, gives a more informative picture of what might need to be addressed for community development. Prosperity is a process, not a static state at a particular point in time.

- Be creative in defining prosperity

Communities are so much more than just their economic base. What makes somewhere a good place to live is a holistic measure of individuals’ work, health, safety, and ability to enjoy life. Isolating to any one indicator and ignoring others will give only a partial picture of what makes a place prosperous. Places are unique, which means their prosperity will also be unique. In many Wisconsin communities, embracing place individuality and exploring new ways of improving well-being is a reflection of the broader, national movement to expand definitions of place prosperity and community livability.

Funding Statement

Financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article comes from the Wisconsin Rural Partnership Initiative at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, part of the USDA-funded Institute for Rural Partnerships and the United States Department of Commerce Economic Development Administration in support of Economic Development Authority University Center [Award No. ED21CHI3030029].

FUNDING STATEMENT

This work was supported by a grant from the United States Department of Commerce Economic Development Administration in support of Economic Development Authority University Center (Award No. ED16CHl3030030 and ED21 CHl3030029). Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Department of Commerce Economic Development Administration.

WIndicators: Wisconsin Farming: Insights from the 2022 Census of Agriculture

WIndicators: Wisconsin Farming: Insights from the 2022 Census of Agriculture WIndicators Volume 5, Number 3: Farm Household Income

WIndicators Volume 5, Number 3: Farm Household Income WIndicators: Labor Shortages, Productivity, and Economic Growth in Wisconsin

WIndicators: Labor Shortages, Productivity, and Economic Growth in Wisconsin WIndicators: The Impact of Housing Financial Stress on Community Well-Being

WIndicators: The Impact of Housing Financial Stress on Community Well-Being