April 2022 — Developing a questionnaire includes two things: the individual questions within the questionnaire and the questionnaire itself. We will start with writing individual questions.

Writing Good Questions

At the most basic level, we have two types of questions: open-ended and closed-ended questions. Open-ended questions allow for qualitative feedback from survey respondents and do not have fixed responses. Close-ended questions ask participants to respond to fixed answers provided by the researcher or practitioner.

Open-Ended Questions

Pros:

- Useful for exploring new topics

- Provides depth to data by allowing respondents to offer more detail and explanation

- Allows respondents to offer clarification on close-ended questions

- Provides high validity

Cons:

- Can be time-consuming for respondents to complete

- May result in very different responses that are hard to summarize and analyze

- Results in low reliability (i.e., lack of consistency in response)

In survey research, you should utilize open-ended questions sparingly. The vast majority of your survey questionnaire should be closed-ended questions. The remainder of this article will explore and describe closed-ended questions.

Types of Closed-Ended Questions

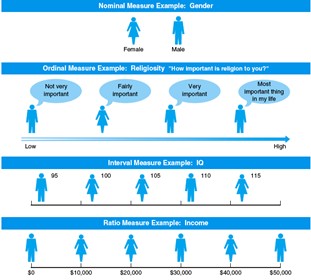

Closed-ended questions fall into four types of questions – nominal, ordinal, interval, and ratio. Each type of question is defined by specific characteristics and has advantages and disadvantages.

Nominal Questions

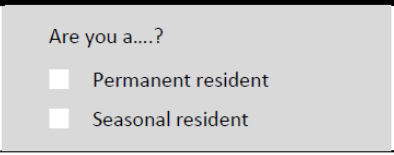

Nominal questions are variables that have the following characteristics. Their attributes (i.e., the response categories) have no ranked order, are exhaustive, and are mutually exclusive. For example, if you ask the question:

This question does not have a rank order, meaning there is no numerical difference between the categories. Also, the question response options are exhaustive in that the respondent should not feel like they can find the category that best represents them. Finally, these categories are distinct from one another (i.e., mutually exclusive), and respondents should be able to choose one over the other.

Ordinal Questions

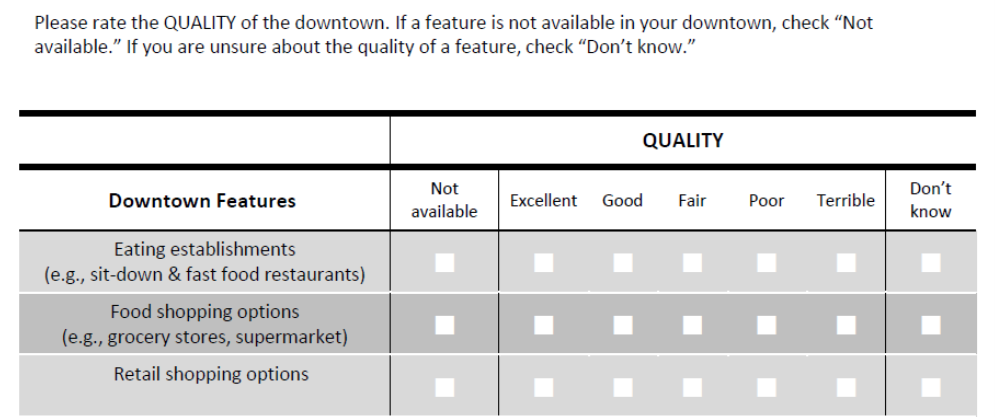

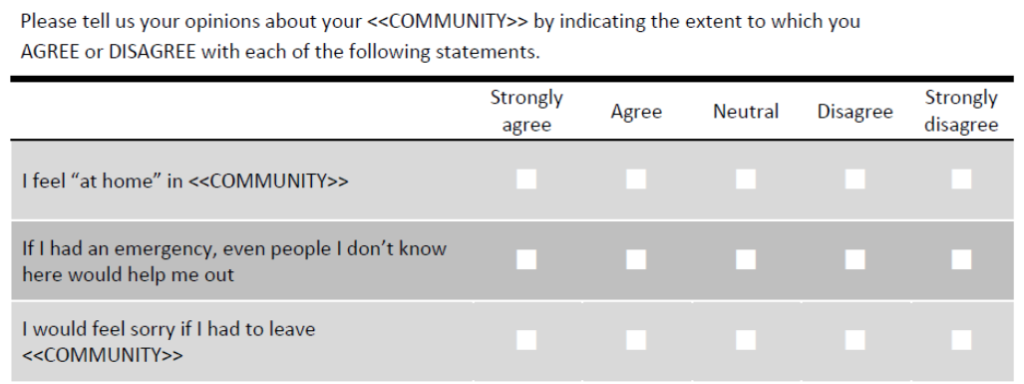

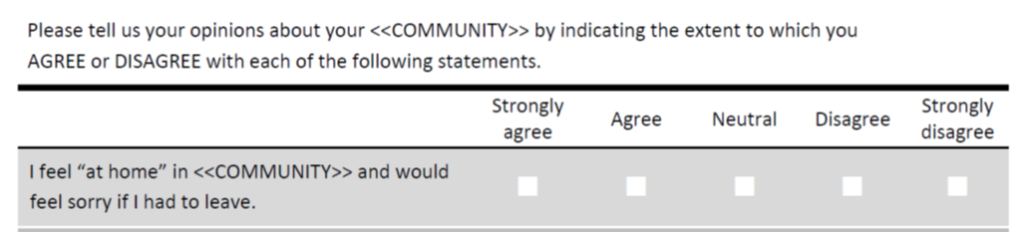

Ordinal questions are variables that share the exhaustive and mutually exclusive traits – that is, respondents should be able to identify only one choice that meets their response. The difference is ordinal level variables have a logical rank order to them. The most common form of ordinal level question used in community-based surveys is the use of the Likert Scale (i.e., the response options for a question fall along the strongly agree to strongly disagree dimension). For example, if you asked the question:

The example above is three ordinal level questions in a matrix format. Respondents should feel like they can adequately respond to these questions with the choices available to them of strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, or strongly disagree and should not feel like they cannot find the answer that best captures their opinion nor like they need to choose more than one option. As a researcher, you can report responses as having a difference in rank order – that is, you can say “X” percent of respondents strongly agree or agree that they feel at home in their community, which is better than the “X” percent of respondents who disagree or strongly disagree with this statement.

Commonly Used Ordinal Scales

- Agreement (strongly agree to strongly disagree)

- Quality (excellent to terrible)

- Satisfaction (very satisfied to very dissatisfied)

- Importance (very important to not at all important)

- Improvement (improve a lot to decline a lot)

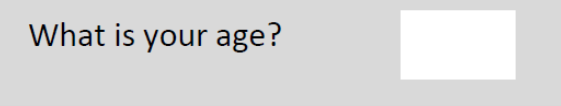

Interval Questions

Interval level questions are exhaustive, mutually exclusive, and have logical rank order to them as well. These questions, however, have one important distinction. The rank order has equal distance between attributes. In the case of an ordinal level question such as a five-point Likert scale, it is impossible to say what is the actual distance between the categorical responses. That is, you can’t say with certainty that the difference between strongly agree and agree is equal to the distance between disagree and strongly disagree. With interval level variables, there is a consistent and equal distance between response options. For example, if you ask the question:

A respondent who answers 37 and another who chooses 38 are one year apart similar to a respondent who chooses 62 and another who states 63 are also one year apart. You will notice this example above is technically an open-ended question. With many interval level questions, this is appropriate because the value respondents report is already numerical, and it would be nearly impossible to include all available choices – e.g., in the case of age, you would use up valuable space to include all possible age choices from 18 (assuming you were only targeting adults) to the oldest known human being.

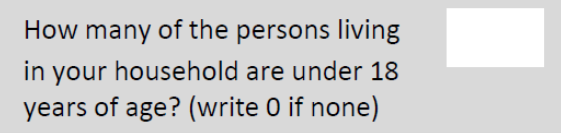

Ratio Questions

The final type of question is ratio level variables. Ratio level questions are exhaustive and mutually exclusive. They also have logical rank order and equal distance between responses. The difference is ration level questions have a true zero, meaning the valid response option is above zero, below zero, or zero itself. For example, you might ask the question:

More commonly, ratio level questions deal with income and wealth but can include behavioral level questions such as time spent doing something. In survey research, researchers often refer to interval and ratio level questions interchangeably.

Tips for Writing Survey Questions

There are several tricks of the trade for writing high-quality questions. Here are some of the most important:

- Questions should be clear, avoiding vague or confusing words or terms, jargon, and abbreviations.

- Keep questions and responses as short as possible. You want respondents to be able to understand the question, identify the responses, choose one, and move on.

- Questions should be complete sentences (e.g., “Age” versus “What is your age?”).

- Response options should be mutually exclusive (only choose one) and exhaustive (no other options).

- Look for “double-barreled questions” (i.e., questions that appear to be one question but are actually two or more).

- Be careful about including unintended bias in the intro and tone of the question (e.g., Many people agree that the downtown is terrible, in your opinion, would you say…).

- Be careful about including unintended bias in the responses. This most commonly occurs with skewed or unbalanced response options. For example, if you ask a question about the quality of the downtown and provide a scale of “excellent,” “good,” “fair,” and “terrible”, you are unintentionally skewing the responses toward the positive response options.

- Only ask questions that respondents can and will answer. In other words, can the respondent reliably answer the question and will the respondent be willing to answer the question?

- Try to avoid questions that include “negative” items such as the word “not”.

Developing a Good Questionnaire

Well done survey questionnaires are like well-written stories. Surveys should flow with transitions and have an introduction, middle, and end. They should be easy for respondents to understand and complete. Survey questions must be carefully worded, double-checked by a fresh pair of eyes, and pretested to ensure they are understood the way you intend them to be. Questions must flow from your area of focus or conceptual design. A poorly worded question will increase the chance of response error and limit the usefulness of the survey data you collect.

Here are some guidelines to consider as you develop your survey questionnaire:

- Layout and Format – the questionnaire should be spread out, easy to read, and aesthetically appealing. This often limits the number and length of questions on a given page and should result in short, concise items per line.

- Flow – the questionnaire should be easy to follow with logical connections between sections that transition nicely. A good rule is to start with a clear introduction and easy to answer questions. Work your way to the more difficult to answer questions that may require more time and effort. Then end with the questions that are either not as interesting but necessary or likely to have lower response rates – e.g., end with the demographic questions including income, age, education, and so on.

- Cover Page – Consider adding a cover page that is attractive and interesting to the respondent (e.g., an easily identifiable image of the place or topic).

- Response Options – Think about how you would like to display the response categories. Do you want them to choose a number or letter? Fill in a circle, or check a box? Are categories easy to see and complete?

- Instructions – Include clear and concise instructions throughout the questionnaire.

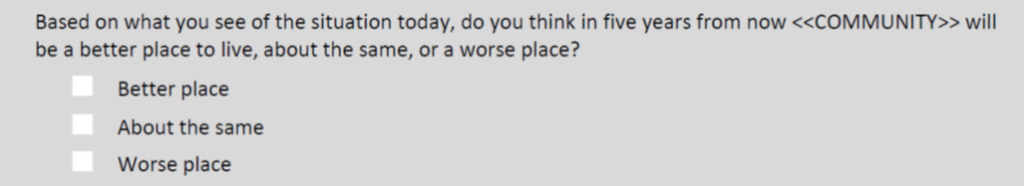

- Transitions – Use transitions between sections – you do not want to confuse respondents and need to be aware of the order of the questions. That is, would answering one question bias the response to another? A good example of this is deciding on the order of individual items versus asking about the respondent’s overall evaluation of something. For example, if you asked:

And then followed this up with a series of questions about the quality of specific parts of the downtown, community features, and recreational amenities, you may get a very different responses. You need to ask yourself, do I want an immediate “gut” reaction to this question, or am I looking for the respondent to evaluate this response after they have really considered the specifics of the community?

- Pilot Test – Most importantly, review and pilot test your survey. You will want to recruit people who are not part of the survey design team to take the questionnaire as if they are a respondent. You will want to interview these individuals, asking them about flow, clarity, question design, formatting, and so on. You want to know where things flowed. Where they might have been confused or frustrated. You want them to flag typos or issues with grammar. The more pretests you do will undoubtedly save you a headache later and will increase the response rate and strengthen the validity and reliability of your questionnaire.

TOP TEN QUESTIONS TO ASK YOURSELF

- What is the fundamental thing or things that you want to learn from the survey?

- Are the questions you have asked likely to generate the information you need to answer the question(s) of interest?

- Are you being parsimonious – asking only the things you need to ask?

- Are you asking about things that are “actionable?” Will the answer to the question enable you to do something (e.g. improve a policy, make a strategic decision for your organization, etc.)?

- Are you asking about things that the survey recipient can reasonably be expected to be able to answer?

- Are you asking things in as neutral a way as possible?

- Are you asking about one thing per question?

- Have you structured your questionnaire in such a way that you can increase the likelihood that the responses you get back really represent the population you are studying?

- Have you included demographic information that can be compared to the census?

- Have you given the respondents a means of telling you things you haven’t thought of? Open-ended questions are more expensive to include in a questionnaire (they take longer to enter and are more difficult to analyze) but can provide very useful context to the numeric answers and raise issues you hadn’t previously identified.

Copyright © 2009 Survey Research Center (SRC) University of Wisconsin, River Falls. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, by any means (electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the SRC

About the Toolbox and this Section

The 2022 update of the toolbox marks over two decades of change in our small city downtowns. It is designed to be a resource to help communities work with their Extension educator, consultant, or on their own to collect data, evaluate opportunities, and develop strategies to become a stronger economic and social center. It is a teaching tool to help build local capacity to make more informed decisions.

This free online resource has been developed and updated by over 100 university educators and graduate students from the University of Wisconsin – Madison, Division of Extension, the University of Minnesota Extension, the Ohio State University Extension, and Michigan State University – Extension. Other downtown and community development professionals have also contributed to its content.

The toolbox is aligned with the principles of the National Main Street Center. The Wisconsin Main Street Program was a key partner in the development of the initial release of the toolbox. One of the purposes of the toolbox has been to expand the examination of downtowns by involving university educators and researchers from a broad variety of perspectives.

The current contributors to each section are identified by name and email at the beginning of each section. For more information or to discuss a particular topic, contact us.