“So unorthodox is the latest batch of demands, introduced only during the latest round of talks, that some question whether the Trump administration is negotiating in good faith. Mr Lighthizer claims to be trying to please only his boss, Mr Trump. But Congress must pass the final deal. This is topsy-turvy. Normally, in America’s trade talks, the president plays nice cop to Congress’s tough guy. This time, roles are reversed. Members of Congress are examining whether it has the legal power to block an attempt to withdraw from NAFTA.” The Economist, October 21, 2017.

The head of the WTO warned about the first signs of a trade war involving the U.S. and China that could derail the global economy, as Europe kept alive a threat to join Beijing in pushing back against President Donald Trump. “We are seeing the first movements toward” a commercial war, World Trade Organization Director General Roberto Azevedo said in an interview posted on the BBC’s website on Wednesday. “It would mean a severe impact on the global economy.” Bloomberg Politics, March 28, 2018.

April 2018 — The Trump Administration has expressed a strong position on current U.S. foreign trade policies. Three strong signals of this position have been to withdraw the U.S. from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), the start of renegotiating the North American Free Trade Act (NAFTA), and the recent announcement of tariffs on steel and aluminum. The notion of free trade between the U.S., Canada and Mexico was first introduced by President Reagan, and signed in 1992 by President Bush and the leaders of Mexico and Canada, creating one of the largest trading zones in the world.

Open trade with foreign markets reflected in current trade policies has a direct impact on the Wisconsin economy. In a 2010 study, Deller found that foreign exports generated about 115,000 jobs in Wisconsin and about $10.5 billion in total income to Wisconsin households. Former Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack wrote in the Wisconsin State Journal (November 25, 2017) “…walking away from NAFTA could deliver a body blow to a dairy industry that is 7.5 percent of Wisconsin’s GDP.” In 2015 (the latest year of available data), 8,634 individual Wisconsin companies exported goods and services outside of the US, 7,419 (85.9 percent) were small and medium sized enterprises with fewer than 500 employees and accounted for 27.4 percent of the dollar value of exports.

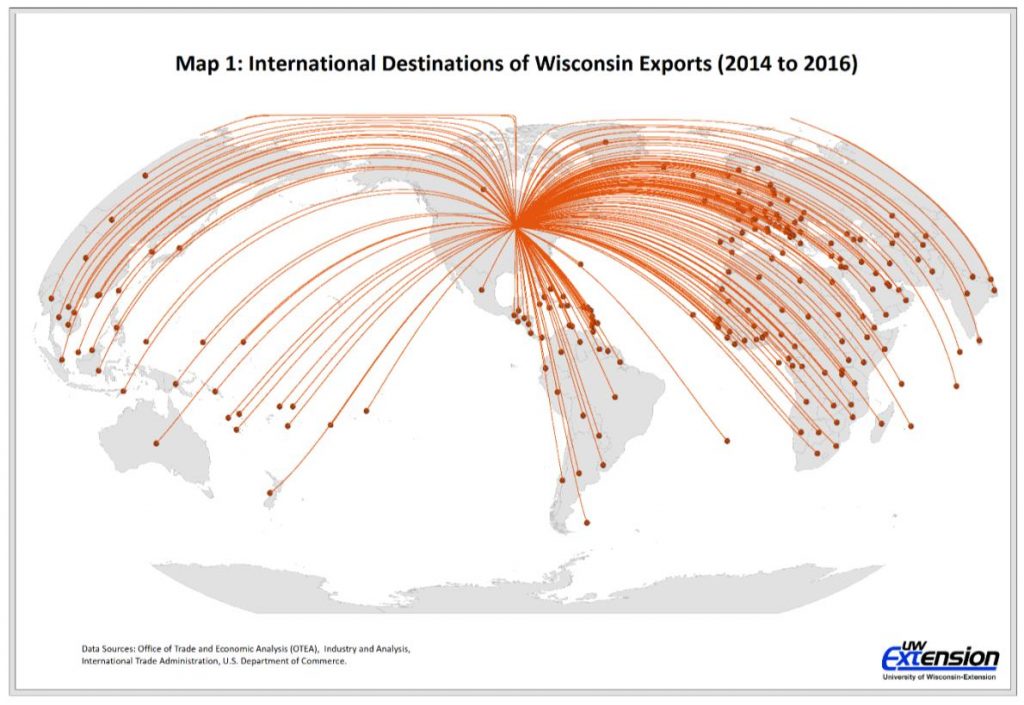

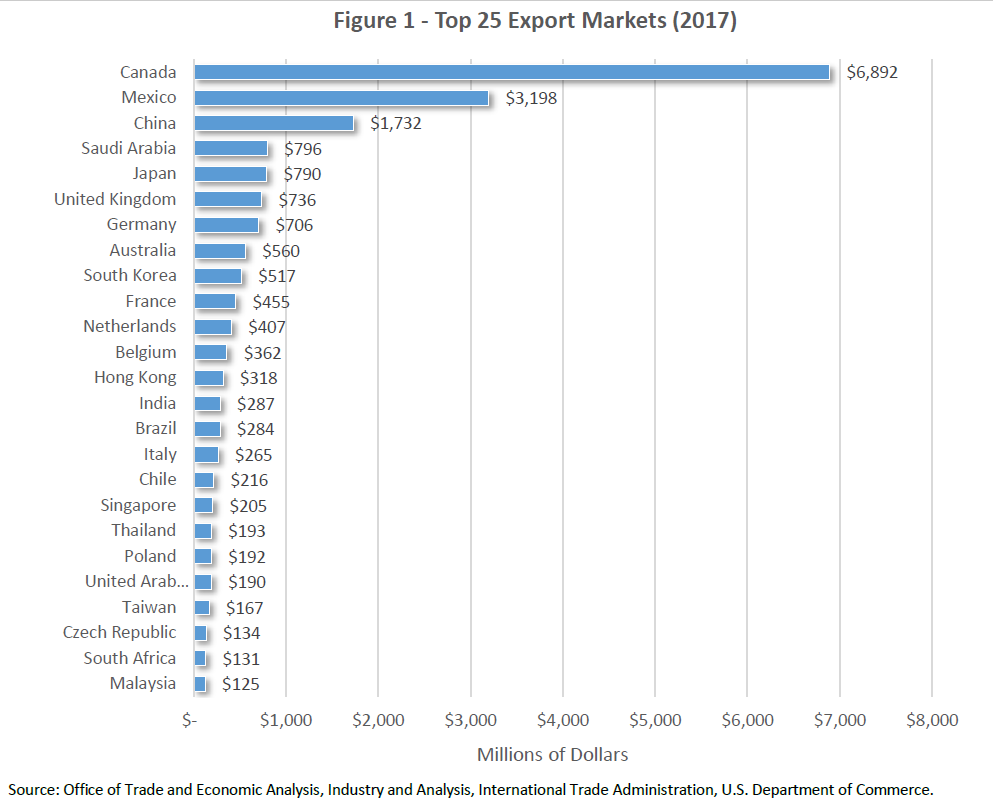

Between 2013 and 2017, Wisconsin had an average annual level of foreign exports of almost $22.4 billion. The largest export market for Wisconsin is Canada with an annual average $7.26 billion over the same period ($6.9B in 2017), followed by Mexico at $2.91 billion ($3.2B in 2017) (Figure 1). Wisconsin’s foreign trading partners expand beyond Canada and Mexico including an average annual $401.6 million to the Netherlands, $257.3 million to Hong Kong, $207 million to Thailand, and $178.2 million to Taiwan Using more detailed export data for 2014, 2015 and 2016, Wisconsin exported to 217 separate countries (Map 1) while Canada, Mexico, China, Japan and the United Kingdom accounted for the top five destinations over this three year period (Map 2).

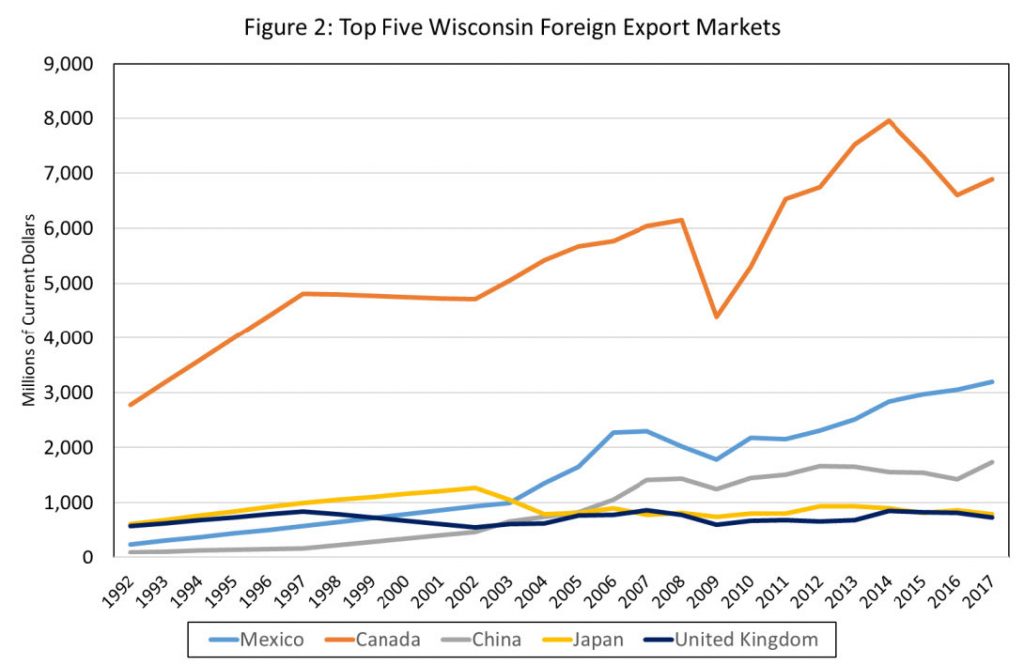

Over a longer period of time (1999 to 2017) we can see a steady upward trend in exports to our major trading partners (Figure 2). In addition to unique changes within individual industries, the year to year fluctuations can be explained by general recessionary pressures and changes in foreign exchange rates. Specifically, if the US economy is stronger than the rest of the world economy, the dollar will rise in value making US exports more expensive thus lowering demand for those exports. At the same time, if the US dollar is weaker, US exports become cheaper thus increasing the demand for those exports. Neither Wisconsin nor Wisconsin businesses have any control over the foreign exchange rates, or the value of the US dollar.

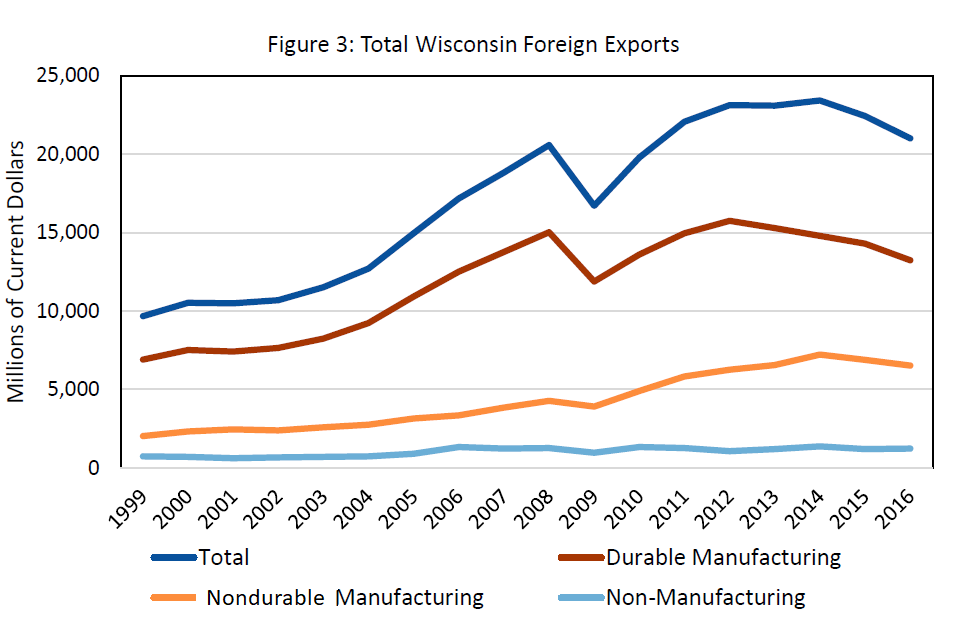

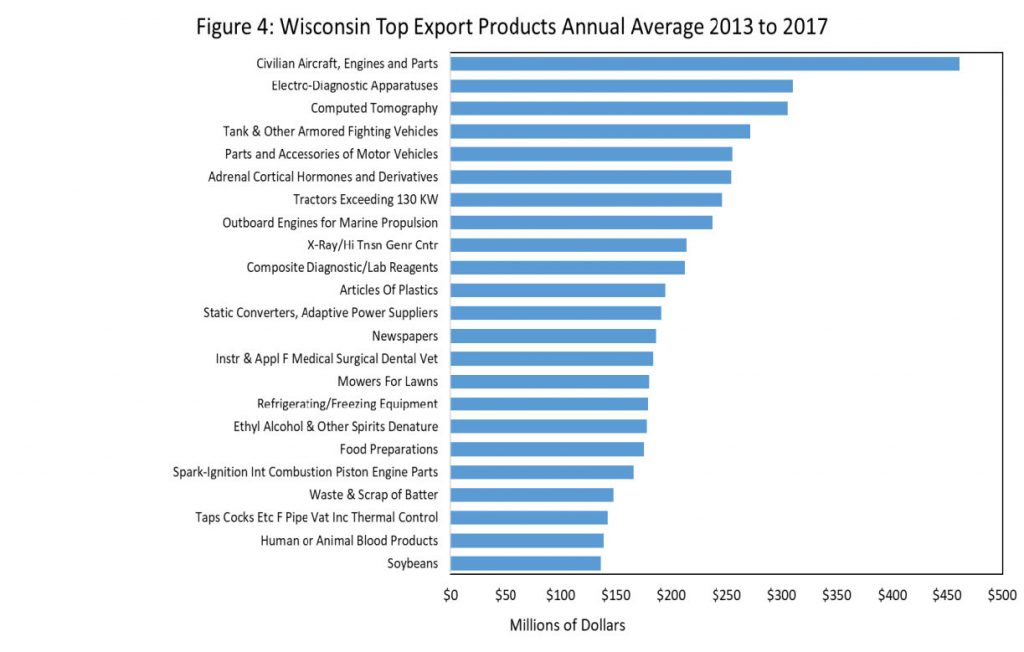

While Wisconsin exports a wide range of goods and services, the market is dominated by durable manufactured goods (Figure 3) including such things as civilian aircraft, engines and parts ($461.1 million annual average between 2013 and 2017), electronic diagnostic equipment ($310.1 million annual average 2013 to 2017), computed tomography apparatus ($305.5 million annual average 2013 to 2017) and soybeans ($136.2 million annual average 2013 to 2017) (Figure 4). While there has been a strong increase in the absolute level of exports for Wisconsin, generally, there has been a noticeable slowdown in recent years, particularly in durable manufacturing (Figure3). The impact of the Great Recession in 2008 and 2009 is clearly evident in the data and recovery to pre-recession levels. Of the top export industries in Figure 4, nine experienced declines between 2013 and 2017, but the remainder experienced increases. While a detailed analysis of why some Wisconsin export sectors are continuing to grow over the past few years and others are declining is beyond the scope of this particular analysis, Wisconsin policy makers need to be aware of these changes.

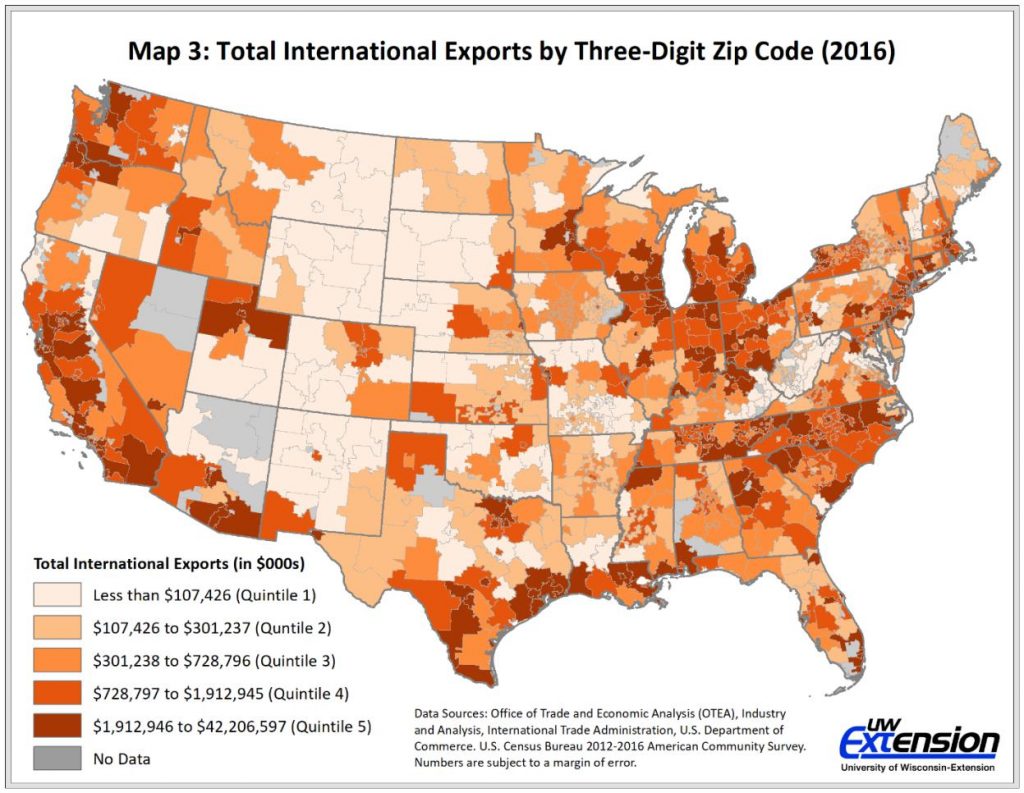

The geographic pattern of dependency on foreign exports reveals that some parts of the U.S. and Wisconsin, are more dependent than others (Map 3). Export levels in some regions make sense, such as Seattle with Boeing, Microsoft, and Amazon; the San Francisco and Silicon Valley region; and large agricultural production found in California’s Central Valley. However, there are other pockets of the U.S. that are less intuitive. For our purposes, the large concentration of high export levels around the southern half of the Lake Michigan region is of particular interest. Much of this region is associated with the traditional manufacturing belt where foreign exports are becoming increasingly important to regional economies. This “export manufacturing belt” includes much of southeastern Wisconsin.

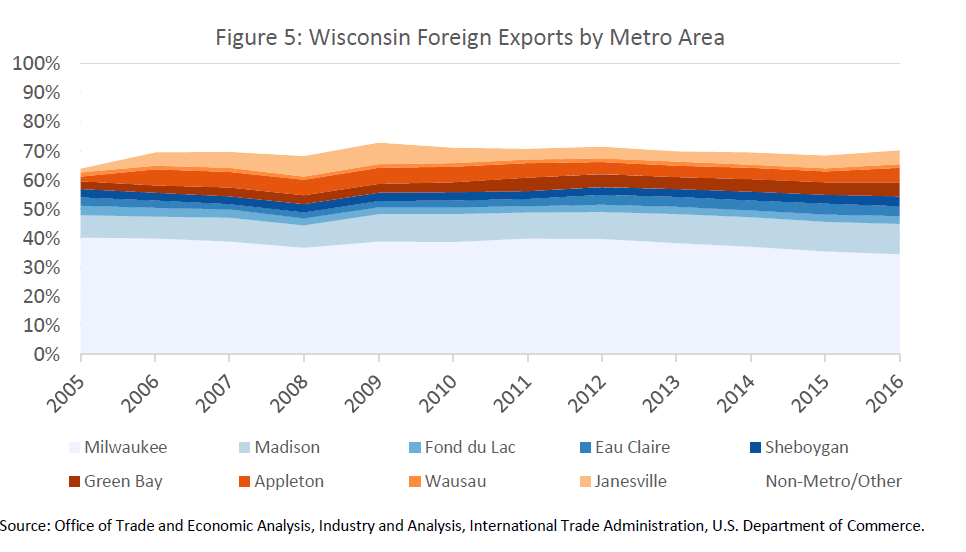

In 2016, the most recent year for sub-state data, the Milwaukee metropolitan area accounted for 34.5 percent of all foreign exports from Wisconsin followed by Madison at 10.5 percent (Figure 5). While the absolute dollar value of exports for the Milwaukee area increased from just over $6 billion in 2005 to $7.25 billion in 2016 the rate of increase for all of Wisconsin has been higher. The result in that Milwaukee’s share of Wisconsin exports declined from 40.2 percent in 2005 to 34.5 percent in 2016. Other metropolitan areas across Wisconsin are assuming a larger share of the Wisconsin export market. For example, the Appleton area accounted for 1.8 percent of Wisconsin’s exports in 2005, but now accounts for 4.9 percent. Similar increases have been seen in the Madison, Green Bay and Janesville-Beloit regions. Much of the decline from the peak in 2012 to 2016 observed in Figure 3, can largely be traced to large declines in Milwaukee exports which went from about $9.2 billion in 2012 to $7.25 billion in 2016, a decline of 20.9 percent. Unfortunately, increases in exports over the same time period for Madison, Sheboygan, Appleton and Janesville-Beloit where not sufficient to offset the declines in the Milwaukee metropolitan area.

Foreign exports are important to Wisconsin, particularly the region from Green Bay to Janesville-Beloit to the Milwaukee metropolitan area. Manufacturing, particularly durable manufacturing, accounts for the majority of exports. But the largest of these sectors falls into what might be called specialized manufacturing such as aircraft parts, and medical related equipment. Agriculture also plays an important part of Wisconsin’s foreign exports ranging from prepared foods (processed foods), soybeans and animal furs. While it is not unexpected that the Great Recession would have a negative impact on exports, the more recent declines, particularly from the Milwaukee region, is less expected.

While sound public policy related to U.S. trade should be constantly reviewed and revised as conditions change, rapid and drastic changes, such as those now being considered by the Trump Administration, must be widely discussed. In order to fully understand the potential impacts of the trade policy changes being discussed on Wisconsin, a better understanding of how trade affects Wisconsin is necessary. For Wisconsin, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) is particularly important as Canada and Mexico are our dominant trading partners. As noted by former Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack, radical changes to NAFTA that restricts free-trade could have large negative impacts on the Wisconsin economy.

References

Deller, Steven C. (2010). “Economic Impact of Foreign Exports on the Wisconsin Economy.” Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Staff Paper Series No. 546, August. https://aae.wisc.edu/pubs/sps/economic-impact-of-foreign-exports/.

Vilsack, Tom. (2017). “Exiting NAFTA Would be a Body Blow to Wisconsin Dairy.” Wisconsin State Journal. November 25, 2017. http://host.madison.com/wsj/opinion/column/tom-vilsack-exiting-nafta-would-be-a-body-blow-to/article_02b49b22-3ca5-55ab-ada0-f5cab764bbfc.html