Volume 7, May 2025

Key Points

- The cost of housing in Wisconsin has been steadily increasing, resulting in more households facing housing financial stress.

- Housing financial stress is more common among renters than homeowners.

- Wisconsin housing financial stress is resulting in negative health outcomes, such as forgone medical care, but this is more likely among older home-owning residents.

OVERVIEW

Housing affordability is a growing concern across Wisconsin and the U.S. at large. Housing costs continue to rise while affordable options are getting harder to find and while job earnings have grown, earnings have failed to keep pace with housing costs. The result is that many households are struggling to keep up with the increasing cost of housing, leading to housing financial stress and increasing instability. While there is no widely accepted measure of housing financial stress, a common method uses a threshold of spending more than 30% of their income on housing. The number of households in the United States and Wisconsin spending over 30% of their income on housing is steadily increasing with no signs of slowing down.

High housing costs can significantly impact the larger community’s health and well-being. Numerous academic studies have documented that housing instability and unaffordability are critical social determinants of health. Studies have shown that living in temporary, unstable, and or unaffordable housing can cause mental and physical stress, leading to food insecurity, physical exhaustion, hypertension, and even falling fertility rates. These stressors are not just individual issues; they affect the broader community’s health outcomes. For example, families struggling to afford housing may face food insecurity, leading to poor diets and increased visits to already strained healthcare services. At a time when communities are actively discussing housing affordability and overburdened health systems, it is important to understand how housing financial stress and health are connected.

In this WIndicator we use a mixed method approach to explore the relationship between housing financial stress and health, focusing on the percentage of people reporting poor or fair health. With a mixed method approach we use a combination of quantitative data analysis to explore the breadth or extent of the housing-health relationship and qualitative interviews to understand why the relationship exists. Our data comes from the 2023 American Community Survey (5-year average) and 22 interviews with residents from 15 different Wisconsin counties. These residents either had firsthand experience with housing financial stress or were housing professionals working to alleviate such stress in their communities. Our findings indicate that for some residents experiencing housing financial stress, they face a trade-off between housing and healthcare with some forgoing healthcare services. This challenge is likely most prevalent among older-homeowning individuals rather than younger renters. This relationship is clear from interviews but more subtle when exploring aggregate or community (county) level data suggesting that while this challenge is acute in some households, the relatively narrow population experiencing this may make it difficult to assess using community level data.

THE COST OF HOUSING

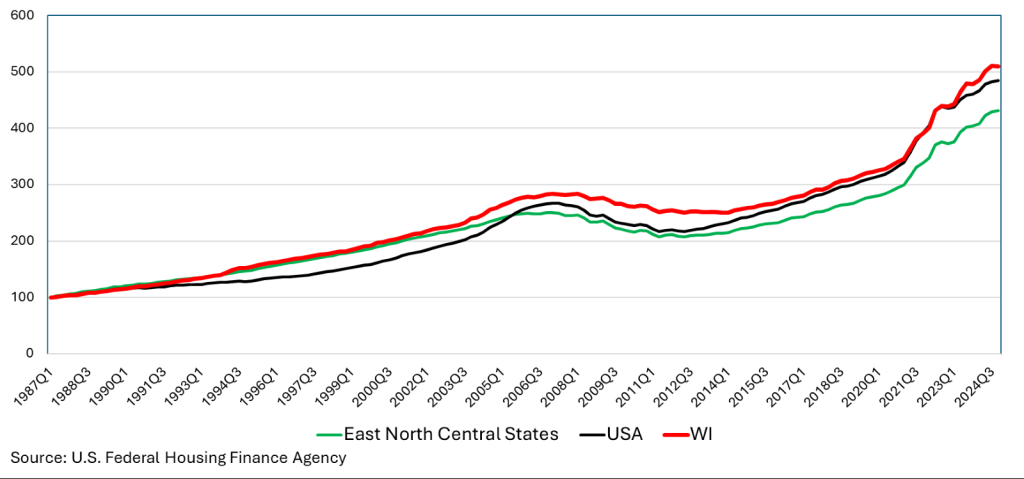

Over the last few years the cost of housing has become increasingly prohibitive across the country, East North Central region of the U.S. (Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio and Wisconsin), and in Wisconsin. Using the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) Housing Price Index, it is clearly evident that housing prices steadily increased in the 1990s and early 2000s with a more rapid increase associated with the housing bubble that peaked in 2007 (Figure 1). During this roughly 15-year period, housing prices nearly tripled in nominal value. While housing prices in Wisconsin increased, the housing bubble was more modest than at the national level. After the housing crises and Great Recession, prices temporarily fell, returning to the longer-term trend line, and then grew relatively modestly for most of the next decade. By 2020, housing prices in Wisconsin had more than regained lost value from the housing crises with the housing price index just above 300 (relative to 1987) at the beginning of 2020. Starting in 2021 the growth in housing prices accelerated and has maintained rapid growth. Most recently, the housing price index in Wisconsin was over 500, indicating a nearly 200-point increase from early 2021 to late 2024.

While the recovery in Wisconsin housing prices immediately after the Great Recession was slower than the national average, starting in 2016 growth in housing prices in Wisconsin have largely tracked with the national trend if slightly higher. Indeed, as of the most recent period in 2024, the housing price index in Wisconsin grew slightly faster than for the whole U.S. Wisconsin stands out more compared to the East North Central region. Compared to the average across these states (Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio and Wisconsin), Wisconsin has consistently faster growth rates in housing price since the start of 2021.

Figure 1 | The FHFA All-Transactions House Price Index (Base Year 1987Q1, Nominal Dollars)

While the increased cost of housing is clear, the extent to which it causes financial stress is harder to define. Measuring “housing financial stress” tends to be somewhat ad hoc with little theoretical foundation for using one method over another. Some researchers use 25% of household income on housing costs, while others use 40%. Others suggest that the thresholds should be adjusted to reflect income. Yet another measure comes from research on banking to determine the appropriate housing price range for a given income: many lenders follow approximation of “three times income” in determining the size of mortgages (Linneman, et.al. 1997; Luengo-Prado, et.al. 2010; Quercia, et.al. 2003). This “3X” rule is widely used by real estate agents to help set the price range for homebuyers. For example, if the total income of the homebuyers is $100,000 then houses priced around $300,000 is a reasonable starting point. Indeed, some have suggested that the relaxing of this “3X” rule was a contributing factor (amongst many others) to the housing bubble if the mid-2000s.

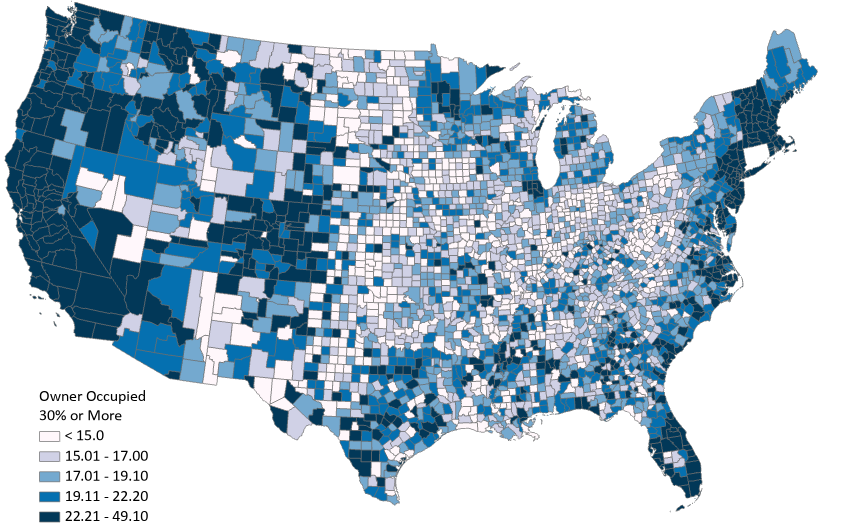

For this study we use the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (2023 5-year average) measure of the share of households spending more than 30% of their income on housing. In the typical county in the U.S., 18.6 percent of owner-occupied households spent 30 percent or more of their income on housing (standard deviation 4.7). In Figure 2, we show the percent of households that spend more than 30 percent of their household income on housing for owner occupied units by county. In the darkest counties more than 22% of households are spending more than 30% of their income on housing. Nantucket County, a county in Massachusetts, has the highest level of owner-occupied financial stress with 49.1 percent spending 30 percent or more of income on housing. On the West Coast, on the Front Range in Colorado, as well as in Florida and parts of the East Coast, especially near New York, this high expenditure is common. In Wisconsin, the typical county has 18.6 percent of owner-occupied households paying 30 percent or more (standard deviation 2.3) of their income with the highest levels of housing financial stress being Jackson (25.2%), Adams (24.9%) followed by Door (24.1%). The Wisconsin counties with the lowest level of stress are Marathon (14.0%), Portage (14.1%), and Outagamie (14.5%).

Figure 2 | Percent Households With Costs 30 Percent or More of Income: Owner Occupied ACS 2023 5-YR Average

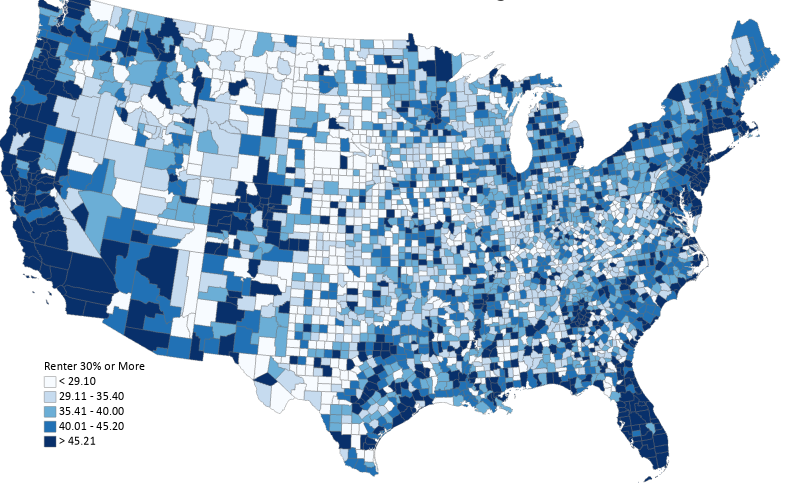

In Figure 3, we consider the same threshold for housing cost, but look at only renter occupied units. Counties where a large share of renters are spending 30% or more of their income on housing are much more common than for owner occupied household, indicating that housing stress is dominated by renters. The typical county in the U.S., 36.9 percent of renter households spend 30 percent or more (standard deviation of 10.0), which is almost double the share of owner-occupied houses paying 30 percent or more. Wahkiakum County, in the State of Washington, has the highest level of renter occupied housing financial stress with 65.3 percent of renters paying 30 percent or more of income to housing costs. Wahkiakum County is a small (population of 4,765 in 2023) county with modest incomes (median income was $30,827 in 2023). In Wisconsin the typical county has 35.0 percent of renters paying 30 percent or more of their income on housing. Lincoln County has the highest rate of rental financial stress with 46.5 percent of renters paying 30 percent or more on housing, followed by Milwaukee (45.6%), Pierce (44.8%) and Dane (44.2%) counties. The Wisconsin county with the lowest rate of renter financial stress is Vilas County were 21.4 percent pay 30 percent or more, followed by Florence (22.6%) and Forest (23.5%) counties.

The distinction between the owner and renter occupied markets is significant. As noted above the level of housing financial stress for owner occupied markets for the typical Wisconsin county is 18.6 percent but for renters it is 35.0 percent. In total, just over 331,300 Wisconsin renting households (44.1%) were experiencing housing financial stress whereas 234,900 Wisconsin owner-occupied households that still had a mortgage (22.9%) were experiencing financial stress. Even those owner-occupied households that did not have a mortgage (39.0 percent of all owner-occupied households), about 91,400 (13.9%) were experiencing housing financial stress. The latter can be explained by non-mortgage related costs such as insurance, utilities and property taxes for those with limited income. These findings indicate that communities that are concerned about strategies to address housing financial stress must include the rental market above and beyond the development of starter homes.

Figure 3 | Percent of Income to Housing Costs: Renter Occupied Units ACS 2023 5-YR Average

IMPACTS IN WISCONSIN

To understand how this housing stress may impact health in Wisconsin, we conducted interviews with Wisconsin residents and conducted a descriptive quantitative data analysis. Together, these mixed methods suggest that high housing costs and associated financial stress can negatively affect health outcomes. At one level high housing costs is often associated with mental stress that can manifest in poor health outcomes and on a more practical level it can prevent people from seeking adequate healthcare because they cannot afford both. Further, while renters face greater housing stress, they are typically younger and are less likely to face trade-offs between healthcare and housing. Though homeowners, on average, experience less housing financial stress, they are typically older and more likely to have health concerns making the trade-offs between healthcare and housing more acute for this demographic.

Insights from In-depth Interviews:

Interviews with community members reveal that housing financial stress may force people, particularly older residents, to prioritize housing expenses over essential medical care, leading to deteriorating health outcomes. Numerous residents reported that high housing costs forced them to allocate a substantial portion of their income to housing, leaving less money available for other essential services such as healthcare. This was particularly pronounced among older residents who are more likely to have limited income, such as Social Security, pensions, and government assistance. Older adults also tend to face more health issues and are more likely to have cooccurring disabilities. However, it is important to note that housing financial stress does not only affect older residents. Younger individuals and families also reported untreated medical conditions, specifically mental health issues, due to high costs of housing, indicating that this issue spans across different age groups.

Forgoing medical care manifested in two primary forms: deferring preventative care and being unable to schedule necessary procedures. Neglecting preventive care included failing to obtain prescriptions, skipping rehabilitation and follow-up appointments, and not maintaining regular check-ups with their therapist and primary care physician due to the costs. Wisconsin residents also reported being unable to secure more urgent medical care, such as necessary surgeries, due to not being able to afford stable housing to recover in.

The implications of forgoing medical care transcended immediate health care needs, potentially impacting the broader well-being of the community. One registered nurse in Portage County described witnessing community members experiencing financial stress related to housing regularly skipping medical care and as a result often end up seeking treatment in emergency rooms (ERs) for conditions that could have been managed or prevented through routine care. These non-emergency visits are significantly more expensive, and further strain hospital resources, making it harder for true emergencies to receive timely care. Since forgoing medical care often disproportionately affects vulnerable residents who are low-income, it can exacerbate health disparities and increase inequality within the community.

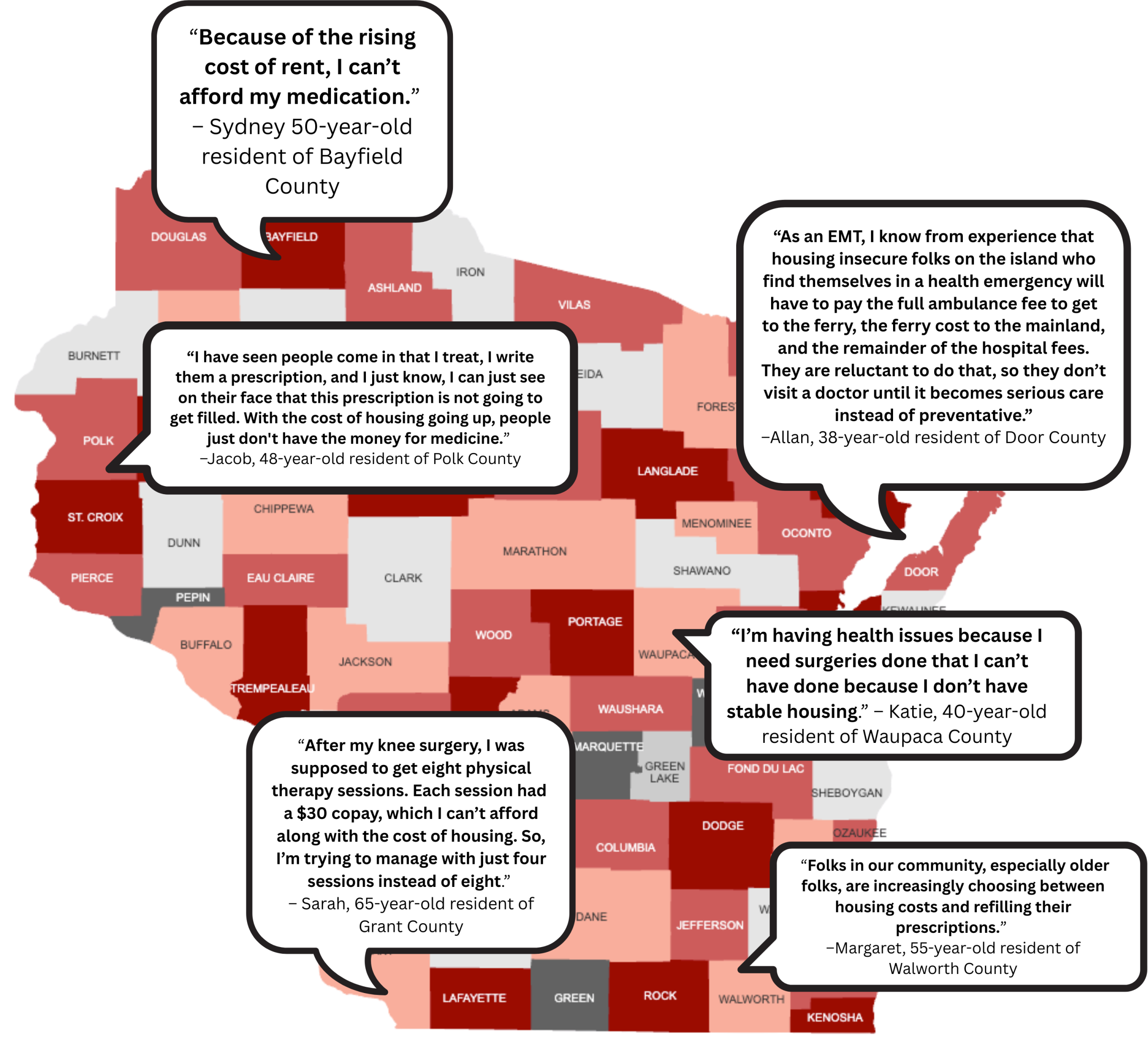

What is notable about this finding is that it emerged organically during the interviews. Our interview guide asked how housing financial stress impacted resident’s health but did not include questions about forfeited healthcare. This insight underscores one of the ways in which housing financial stress can contribute to poor or fair health. To illustrate how housing financial stress can lead to poor health participant quotes are highlighted in Figure 4.

Figure 4 | Quotes from interviews with community members in Wisconsin.

Source: Interviews were conducted between February and April of 2025 as part of a larger IRB approved study on the impacts of housing stress on rural community well-being. Names and locations have been changed to protect the confidentiality of participants.

Insights from Quantitative Data Analysis:

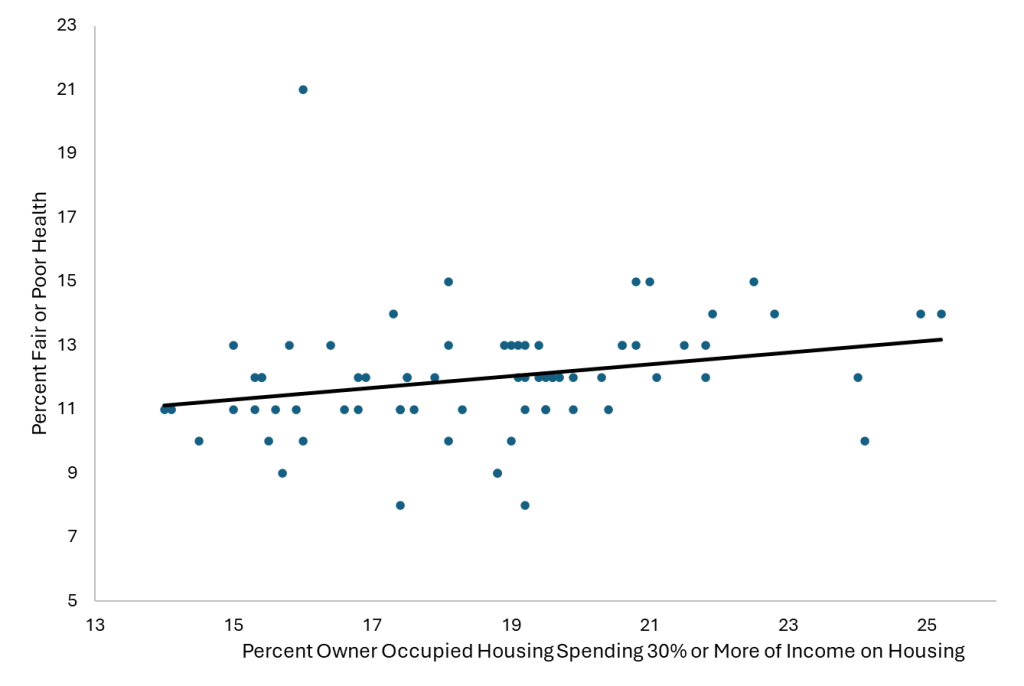

Given the insights from the interviews, we considered the relationship between housing and health outcomes at the community-level for Wisconsin counties. Do housing challenges result in population-level changes in health? To better understand this relationship, we plot the housing financial stress variable against the share of the population self-reporting that they are in poor or fair health by county for all 72 Wisconsin counties (Figure 5). The health measure here is drawn from the County Health Rankings maintained by the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute which in turns draws the data from the U.S. Center for Disease Control’s Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.

Based on the Wisconsin county-level data, we see a weakly positive relationship between housing financial stress among owner-occupied houses and the share of people reporting fair or poor health. This relationship suggests that greater housing financial stress corresponds to a larger share of the population in fair or poor health (Figure 5). This finding is consistent with the insights gained from the interviews and suggest that financially induced mental and physical stress coupled with forgone healthcare is having a negative impact on community well-being. It is important to note, however, that the relationship may appear to be modest due to many causal factors that could be co-determining these outcomes.

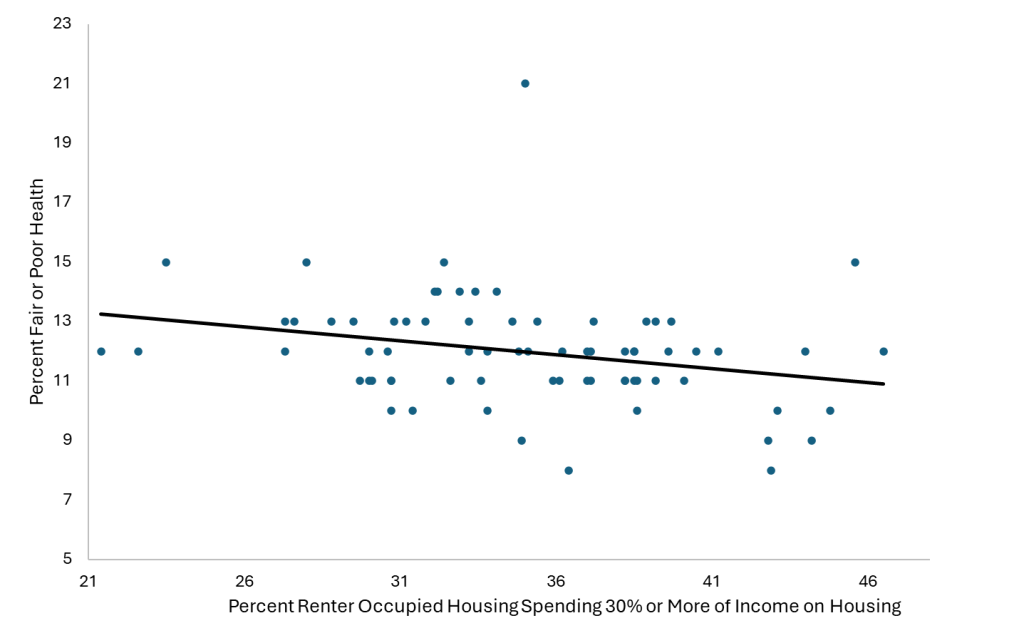

In Figure 6, we plot the same relationship for renter-occupied units and see a slight negative relationship, implying that high levels of housing financial stress among renters is associated with a smaller share of the population in fair or poor health. While this may seem incompatible with the interview findings, this is likely due to the relatively young profile of renters compared to homeowners who therefore tend to have fewer health issues. More than three-quarters of those 55 and older own their home whereas less than 40% of people under 35 years old own their home (Callis, 2023). As a result, even though housing stress is more common among renters, the relationship between health and housing challenges is likely more pronounced among the older home-owning segment of the population. In other words, the relationship between housing financial stress and well-being, as defined by our simple health measure, is an interplay between age, income, housing financial stress.

Figure 5 | Percent of Owner Occupied Houses Experiencing Housing Financial Stress and Percent Fair-Poor Health: Wisconsin Counties

Figure 6 | Percent of Renter Occupied Houses Experiencing Housing Financial Stress and Percent Fair-Poor Health: Wisconsin Counties

CONCLUSION AND IMPLICATIONS

Financial stress flowing from increasing costs of housing is a significant concern for large parts of the U.S. as well as Wisconsin residents. This is particularly true for older homeowners, as many live on limited incomes and face overlapping health issues, but younger residents and families are also impacted. Our interviews with Wisconsin residents reveal that housing financial stress can force people to prioritize housing expenses over essential medical care, leading to deteriorating health outcomes. The lack of affordable housing options exacerbates this issue, making it difficult for people to find suitable living arrangements that meet their needs. Addressing these housing challenges is crucial to ensure the health of Wisconsin residents of all ages and the well-being of their community.

While our findings shed light on the impact of housing financial stress on community well-being, they also reveal the limitations of aggregate analysis. Community level analysis may be too broad to accurately capture how housing financial stress impacts health. Aggregate data identifies patterns and correlations but tends to smooth out individual variations and contextual nuances, making it difficult to discern specific impacts, such as specific ways housing financial stress impacts health. The American Community Survey does not include questions about forgoing medical care, which is why these details are not visible in our aggregate data. To understand the effects of housing financial stress on health, a micro, individual level analysis is essential. The finding on forgone healthcare underscores that critical trade-offs faced by individuals experiencing housing financial stress may be missed when using community level data.

POLICY IMPLICATIONS

Based on these findings, we offer several suggestions that community development professionals can pursue locally:

- Housing Task Forces with Healthcare Representation: Ensure that hospitals and clinics are represented on local housing task forces. This collaboration can help integrate health perspectives into local housing initiatives, ensuring that housing solutions also address health needs.

- Community Health Partnerships: Establish partnerships between healthcare systems and community development organizations. These collaborations can focus on addressing social determinants of health, such as housing, education, and employment.

- Supportive Housing Programs: Develop supportive housing programs that provide both housing and healthcare services for elder adults and individuals with chronic health conditions, mental health issues, and substance use disorders.

- Joint Training Programs: Develop joint training programs where housing service staff and healthcare providers learn together about the social determinants of health. This can help both sectors understand the broader impacts of housing instability on health and work collaboratively to address these issues.

- Case Management Collaboration: Implement cross-sector case management teams that include housing service providers and healthcare professionals. These teams can work together to provide comprehensive support to individuals facing housing instability and health challenges.

- Community Outreach Programs: Implement community outreach programs that educate residents about the importance of stable, affordable housing for health, especially for seniors in the community. These programs can also offer resources and assistance to individuals experiencing housing instability.

- Collaborative Funding Initiatives: Work with local governments and nonprofits to secure funding for projects that address both housing and health needs. Collaborative funding can help ensure that resources are allocated effectively to improve community well-being.

To learn more about the relationship between health and housing:

Antin, Tamar Mj, Emile Sanders, Sharon Lipperman-Kreda, Geoffrey Hunt, and Rachelle Annechino. 2024. “An Exploration of Rural Housing Insecurity as a Public Health Problem in California’s Rural Northern Counties.” Journal of Community Health 49(4):644–55. doi: 10.1007/s10900-024-01330-z.

Baker, Emma, Laurence Lester, Kate Mason, and Rebecca Bentley. 2020. “Mental Health and Prolonged Exposure to Unaffordable Housing: A Longitudinal Analysis.” Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 55(6):715–21. doi: 10.1007/s00127-020-01849-1.

Braveman, Paula. 2023. “Housing, Health, and Health Disparities.” Pp. 205–26 in The Social Determinants of Health and Health Disparities. Oxford University Press.

Callis, Robert R. (July 25, 2023). ” Rate of Homeownership Higher Than Before Pandemic in All Regions.” U.S. Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2023/07/younger-householders-drove-rebound-in-homeownership.html

DeLuca, Stefanie, and Eva Rosen. 2022. “Housing Insecurity Among the Poor Today.” Annual Review of Sociology 48:343–71.

Gershenson, Carl, and Matthew Desmond. 2024. “Eviction and the Rental Housing Crisis in Rural America.” Rural Sociology 89(1):86–105. doi: 10.1111/ruso.12528.

Pollack, Craig Evan, Beth Ann Griffin, and Julia Lynch. 2010. “Housing Affordability and Health Among Homeowners and Renters.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 39(6):515–21. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.08.002.

U.S. Census Bureau. 2024. “Nearly Half of Renter Households Are Cost-Burdened, Proportions Differ by Race.” Retrieved (https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2024/renter-households-cost-burdened-race.html).

Funding Statement

Financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article comes from the Wisconsin Rural Partnership Initiative at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, part of the USDA-funded Institute for Rural Partnerships and the United States Department of Commerce Economic Development Administration in support of Economic Development Authority University Center [Award No. ED21CHI3030029].

Lac du Flambeau Housing Summit

Lac du Flambeau Housing Summit 2022 Wisconsin Housing Symposium

2022 Wisconsin Housing Symposium Housing

Housing WIndicators Volume 4, Number 3: Seasonal and Recreational Housing Units in Wisconsin

WIndicators Volume 4, Number 3: Seasonal and Recreational Housing Units in Wisconsin