April 2022 — A market analysis should include local survey research to fully understand the uniqueness of your particular market and its consumers. Consumer surveys can provide information on when, where, why, how, and for what people shop, dine, live, work, and recreate. They can reveal attitudes toward your downtown and how those attitudes affect shopping and dining habits. Surveys also invite consumers to share their perspectives regarding the current and future economic health of a downtown or business district. Readily available demographic or lifestyle data from secondary sources described earlier in this toolbox cannot completely describe where local people shop or what they would like to see in their downtown.

This section provides details on what kinds of surveys and questions could help your analysis and provides samples of survey instruments for your use.

Conducting Survey Research – An Overview

Community Economic Development practitioners use surveys to obtain data to assess trends and conditions, advance understanding, test theories, develop policy recommendations or business strategies, and much more. Surveys can be conducted by questionnaire (in writing or online) or by interview (by phone or in-person).

One example of a survey is the nationwide poll conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau every 10 years. The census is unusual in that it seeks to query every member of its population base, i.e., every resident of the country.

More commonly, surveys rely on the responses of a sample population to gauge the feelings of a larger population. Two common examples are surveys to capture public opinion (used by the media and elected officials or government) and surveys to assess consumer preferences and interests (used by businesses and marketing firms hired by businesses). In our context, surveys are a way to understand consumer needs by going beyond the information collected through demographic and lifestyle data from a secondary source.

As in all science, survey measurement is not error-free. Procedures used to conduct a survey have major effects on outcomes. Therefore, your goal as an analyst is to choose the most appropriate survey procedures that, when applied, will reduce error and maximize the accuracy of what is measured.

Types of Error in Survey Research

Researchers and applied practitioners try to minimize errors whenever possible. When conducting survey research, there are four primary areas where error most likely occurs: coverage error, sampling error, measurement error, and nonresponse error.

- Coverage error refers to an incomplete list of the population. For example, if you are looking to survey households in a community but your list only has homeowners, you will have an issue with leaving out renters.

- Sampling error refers to unintentionally missing a subset of the population. If your final sample does not reflect the population you will increase the likelihood of sampling error.

- Measurement error is when the observed value does not reflect the actual value. In other words, the answer you received from a survey questionnaire either does not represent the actual answer within the population, or the question you asked does not measure what you claim it does. The former is a problem tied to sampling and the latter is connected to the intent and design of the question.

- Nonresponse error occurs when certain segments of the population are less likely to complete the survey or sections of the survey.

A community-based survey effort has seven key components:

- Identifying the Project Focus

- Sampling

- Designing the Questionnaire

- Collecting the Data

- Entering the Data

- Interpreting the Data

- Communicating Results.

Following best practices in each component will enable a community to make more informed decisions. In this section we will both provide textbook-style definitions of survey procedures, then explain how they work for community and business leaders seeking to assess their business environment. We will also discuss each procedure in the context of solving the example questions presented in the hypothetical community, “Anytown”.

Anytown Example

The leaders of “Anytown” are interested in improving retail sales in their central business district. They ask you to identify the factors that determine where local residents do their shopping. Consequently, you put together a survey research program that seeks to understand this research question. You envision surveying a sample of consumers to obtain information on their shopping preferences and behaviors. Following the seven key components, here’s how a survey research program can be implemented in Anytown.

Identifying the Project Focus

One of the most important decisions researchers and applied practitioners need to make is at the beginning of the research process. Deciding what the focus of the project will be. This decision defines the trajectory of all other choices. It is crucially important that you identify the core concepts you hope to understand and the information you are hoping to collect. Researchers refer to this process as conceptualization.

Conceptualization

Conceptualization refers to defining and specifying what a researcher or practitioner means by a specific term or word. Articulating what one means by a given concept helps establish the purpose of a research project and clarifies what is hoping to be measured and eventually understood. This process allows outsiders to see what the researcher is doing and how they are thinking about the central concepts.

Anytown Example

As you begin the process of designing your survey program, you return to the central focus of the project, improving retail sales in the central business district. There are two avenues you consider for improving retail sales – expanding existing businesses and attracting or creating new businesses in sectors Anytown currently does not have. To capture the consumer wants and needs, you decide to identify the factors that determine where residents do their shopping, their current wants and needs, perceptions of availability and quality of options, and key demographic characteristics.

Sampling

Sampling consists of selecting a small portion of a population to represent the whole population. It is this sample that you would survey. When sampling, you need to give all members of the population the same chance of being selected.

The very first thing you need to decide is what is your target population. This decision may seem straightforward, but wrong answers can limit what you can communicate about your findings. For example, are you hoping to survey shoppers? Community members? Households? Each target will produce potentially different results and run the risk of sampling or coverage error. If you choose shoppers, your population goes far beyond the boundaries of the community and requires a different sampling frame and sampling design. If you want community members, you may miss out on shoppers and run the risk of oversampling a household by choosing two people from the same home, which may bias the results. If your target is households, how do you identify who completes the survey and from what perspective, i.e., themselves or on behalf of the household? The “right” answer depends on your focus or goal.

Important Terms

Population refers to the entire group of something (e.g., all people in a community, all shoppers downtown, all business owners in the county).

Sample is a specific group selected from the population and the group that will complete the survey questionnaire.

Sampling frame is the list of the population from which the sample will be drawn. The ideal sampling frame is identical to the population.

Sampling design refers to the strategy or plans to identify those selected for the sample. Sampling designs fall into two camps, probability and non-probability-based sampling designs.

- Probability-based sampling is defined by elements of the sample having an equal chance of selection resulting in representativeness and generalizability.

- Non-probability-based sampling does not guarantee an equal chance of selection to elements of the population and therefore is not representative nor generalizable.

Representativeness refers to the sample reflecting the same characteristics and variations as the broader population.

Generalizability refers to the confidence one has to make statements about the population based on findings from the sample.

Anytown Example

Considering the focus of your project and your budget, you decide to survey a sample of area residents by written questionnaire. Since you do not want your entire sample to come from the same neighborhood or demographic sector, you want to give all residents an equal chance of being chosen. You decide to randomly pick a sample of 1,200 owner-occupied and rental addresses in Anytown’s convenience trade area.

Designing the Questionnaire

Well done survey questionnaires are like well-written stories. Surveys should flow with transitions and have an introduction, middle, and end. They should be easy for respondents to understand and complete.

Survey questions must be carefully worded, double-checked by a fresh pair of eyes, and pretested to ensure they are understood the way you intend them to be. Questions must flow from your area of focus or conceptual design. A poorly worded question will increase the chance of response error and limit the usefulness of the survey data you collect. Designing good survey questions involves selecting those needed to meet the research objectives, testing them to make sure they can be asked and answered as planned, then formatting them to make it easy for interviewers to ask them and for respondents to answer them.

Important Terms

Operationalization is an extension of conceptualization. It refers to moving from the abstract to the specific and measurable. In other words, you are taking ideas and trying to find a way to measure and capture that idea in the real world through empirical observation (i.e., a survey question).

Validity refers to the accuracy of a question to capture the meaning of a concept. If you want to understand shopping behaviors downtown, you need to ask questions such as how often do you buy certain goods, from where do you buy them, how much do you buy, and so on.

Reliability is related to the consistency in obtaining the same results at different times. For example, if you are interested in shopping behaviors, you will want to ask questions that allow the respondent to answer the same each time. You would want to ask “how much milk did you buy last week?” versus “how much milk did you buy last year?”. The former question is much easier for the respondent to recall and to consistently respond with a dependable answer.

Anytown Example

Now that you have selected your sample, you are ready to design the survey questionnaire itself. You decide not to hire a professional survey designer for budgetary reasons, so you instead search the web and ask around about communities that pursued a survey research program similar to the one you are commissioned to do. You found that Othertown ran a similar survey research program and is willing to share their questionnaire with you. Since Othertown has different amenities, you modify its questionnaire to reflect both the objectives of your research agenda and the different business environment of your community.

For a more comprehensive approach to data collection, you include both quantitative (forced-choice questions, such as yes or no, or true or false) and qualitative questions (open-ended questions that give respondents a chance to write their thoughts and feelings). After clearing the survey instrument of any possible confusion and receiving feedback from all your collaborators, you decide to test it by sending it to 10 consumers of Anytown who you know personally and who are not part of your sample. After receiving honest feedback from your 10 “testers” and making any necessary changes, you are ready to send out the survey to your sample of 1,200 residents.

Collecting the Data

Survey research is an excellent methodological tool to collect original data covering a large population on a relatively quick timeline. You can use surveys to collect information on nearly any community issue. Survey research can provide generalizable information about the behaviors, opinions, attitudes, and values of a population at a low cost. And they can be administered by mail, telephone, online, or face-to-face. Your budget and sampling design will determine how you send out your survey. You must use good judgment to identify the survey method or methods based on project objectives, the sensitivity of questions, and the budget.

Types of Consumer Surveys

There are four basic ways to survey consumers: mail surveys, telephone surveys, web-based surveys, and intercept (or face-to-face) surveys.

Mail Surveys

Mail surveys (questionnaires) involve printing and distributing questions to consumers via mail. Use a mail survey if you want to collect comprehensive consumer information. You must keep mail surveys short, or if you need to ask a lot of questions, format and organize them in such a way that encourages consumers to complete them.

Telephone Surveys

Telephone surveys are a technique where interviewers call consumers to ask questions. Use a telephone survey if you want to collect specific information that can be difficult to obtain in written surveys.

Web-Based Surveys

Web-based (online) surveys involve programming and emailing a web-based set of questions to consumers. This method can include many of the same questions and formats as written and telephone surveys. Depending on the type of data needed, online surveys can be specific or comprehensive in nature.

Intercept (and Face-to-Face) Surveys

Intercept surveys are a technique where you stop a representative sample of downtown patrons on the street or at their point of purchase and ask questions. Use an intercept survey if you want to collect specific consumer information from users of the downtown.

Anytown Example

After considering the pros and cons of the various modes of data collection, you decide to conduct a mail survey. A week before mailing the actual questionnaire, you send a letter to your sample explaining the survey and its importance to the betterment of Anytown. Since their participation is voluntary, you include an incentive to encourage them to complete and return the questionnaire promptly. You include the same letter when you mail the actual survey one week or so later and emphasize the importance of returning the survey by the deadline. The deadline you provide is approximately two weeks before the deadline you set for yourself to start analyzing the data. After the deadline passes, you send another reminder to those in the sample that have yet to respond and you include another questionnaire just in case they misplaced the previous one. After all the data has been collected, coding may be necessary for use in computer software programs and to protect the confidentiality of the respondents. Coding may also enable easier transfer of data to other users.

Entering the Data

After collecting the data, it is crucial to establish a way to keep information organized that allows for further analysis. Data entry can be recorded manually by user entry, use of optical scanners, or through online programs such as Qualtrics or SurveyMonkey. If you use an optical scanner or an online survey collection program, your data will already be organized and require minimal cleaning. However, if you collect your data via paper survey, you will need to enter the data into a database you set up. Data is most often organized in software such as Excel and statistical analysis programs such as SPSS or R.

Setting Up Your Codebook And “Database”

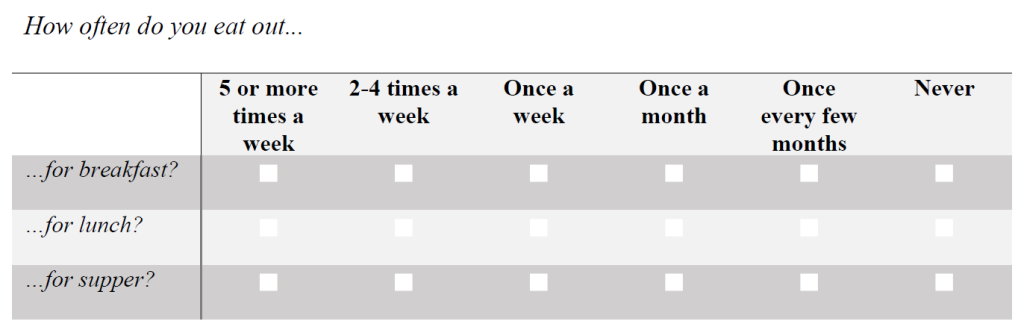

Although not officially a database, Microsoft Excel makes it easy to organize and analyze your data. One way to move your survey questionnaire into Excel is to establish a codebook, or a document that clearly shows what numerical values mean in your “database” and explain the detailed description of variable names. For example, if you ask the question matrix:

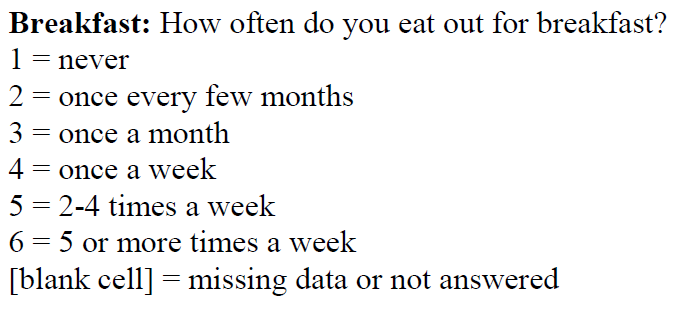

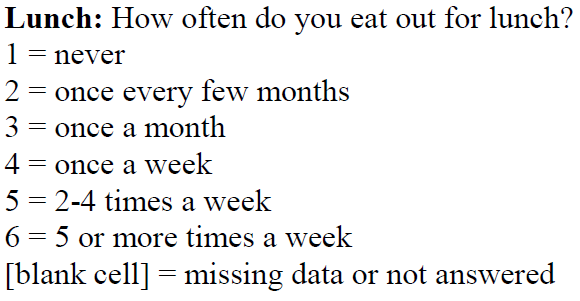

You would want to turn this survey question into a readable codebook item. The first thing you will notice is that this is not one but three questions (i.e., breakfast, lunch, and dinner). As such, you will want to create a short variable name. Next, you will need to assign a numerical value to the attributes (i.e., the options the respondents can choose). Finally, you will need to decide how you want to deal with missing data, meaning the respondent did not answer the question. Here is how you turn this question matrix into an item in your codebook:

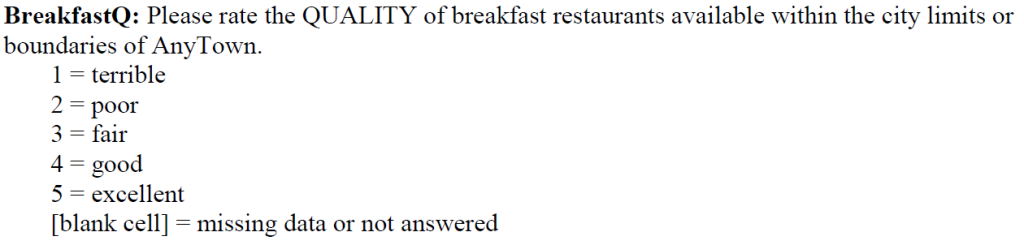

When deciding what value to assign, you have a couple of things to keep in mind. First, you want to be sure to keep scales going in the same direction. For example, if you decide that the more often people eat out should have a “larger” number assigned to it, you will want to do the same for all questions throughout your survey. Maybe your survey includes a question about the “quality of existing restaurants in town” rated on a scale of “excellent” (=5) “good” (=4), “fair” (=3), “poor” (=2), and “terrible” (=1). To minimize headaches and work later and to allow for more sophisticated analysis, you will want to make sure to assign higher numbers to the more positive ratings.

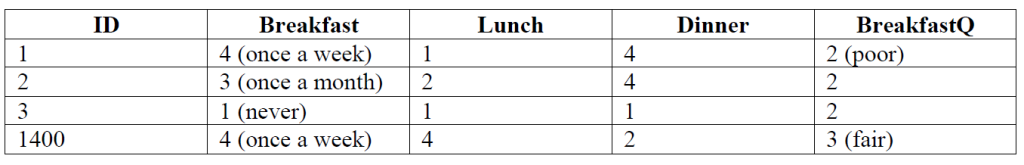

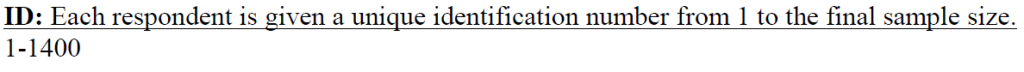

Finally, do not forget to include a variable in your codebook for the respondent. This will sync with your “database” and provide easy access to check and clean data. Here is an example of how to set this up:

Once you have completed this process for the entire survey questionnaire, you can set up your “database” and begin data entry.

Interpreting the Data

Once you deem the dataset complete, you can begin using it to address the research questions previously identified. For survey research, you may want to calculate the average, mean, median, or variance. Or you may want to estimate the association between and among key variables of interest. Such analyses can be done using software such as Microsoft Excel, SPSS, Stata, SAS, R, and others.

Quick Primer to Basic Analysis

Basic data analysis includes simple univariate analysis and bivariate analysis. Univariate analyses examine a single variable within a dataset and are used to describe the characteristics of the sample. There are several ways to evaluate a single variable including measures of distribution, central tendency, and dispersion.

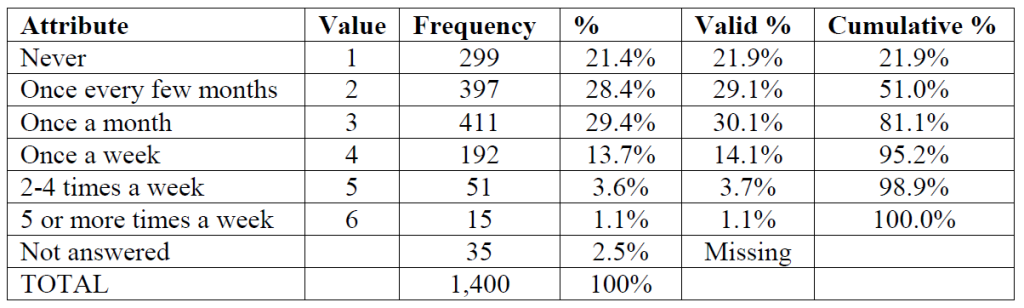

Frequency distributions refer to showing response by count and percent per variable attribute. For example, if you have asked 1,400 respondents to answer the question, “How often do you eat out for breakfast?” on a scale from “never” to “5 or more times a week”. You can examine responses in a frequency distribution table:

Measures of central tendency include mean (average), median (middle point), and mode (most common). The mean is calculated by adding all values of all responses and dividing it by the total number of responses. The median is calculated by taking the middle two numbers, adding them together, and dividing this number by 2. The number you get is the 50th percentile, suggesting that half of the responses fall below and half fall above. Finally, mode is simply the most common response and can be found by reviewing frequency distributions.

Dispersion is a way to understand how responses are distributed around a central point such as the average or mean. The simplest measure of dispersion is range, which is the difference between the lowest and highest value within the sample. For example, if your youngest respondent is 18 years old and the oldest is 88, the range is 70. Common measures of dispersion that require more sophisticated analysis and interpretation are variance (i.e., a statistic that provides insight into how wide the spread is from the mean) and standard deviation (i.e., a statistic that provides insight into the variability in a dataset as it relates to a normal, or bell-shaped, curve).

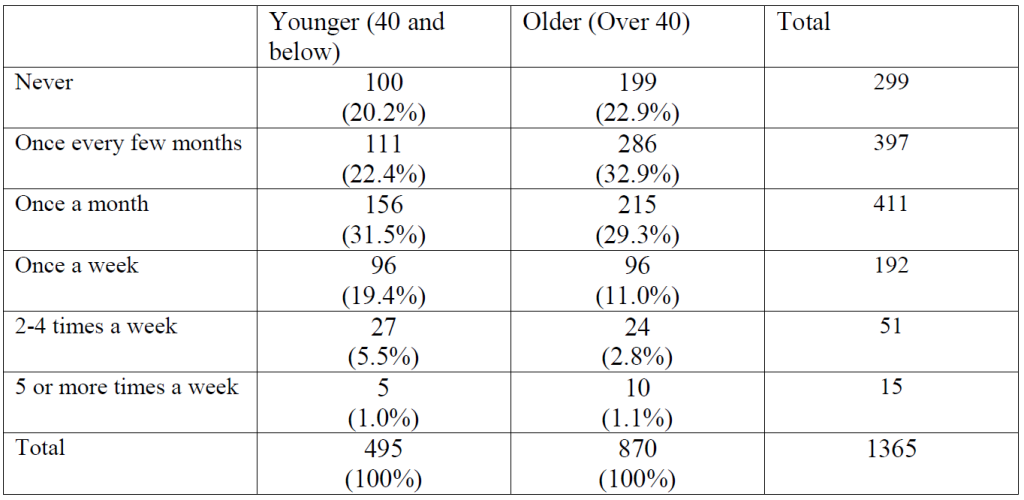

Bivariate (and multivariate) analysis starts the process of examining how variables relate to one another. The simplest method is to place data in a table that shows how one variable is distributed by the responses of another variable. For example, if you wanted to examine how the frequency of eating breakfast out is distributed by age, you could set up the following table:

*note, missing data has been removed from the analysis and percentages are calculated within the age category.

*note, missing data has been removed from the analysis and percentages are calculated within the age category.

One can start to understand a lot about the sample by using cross-tabulated tables such as the one above. It will show if and where there are major differences by attribute. There are more advanced analyses that will further explore the associations between variables and can help answer questions such as do these two variables seem to increase or decrease with one another? What is the strength of the relationship between these two variables, if any? Common advance analyses include correlations (i.e., a measure of association between two variables), Chi-square (i.e., a test of variable dependence/independence), t-test (i.e., a specific test between the mean score for two groupings/attributes – e.g., is the average amount of times “younger” respondents eat out meaningfully different than the average amount of times “older” respondents eat out), and One-way ANOVA (i.e., test that examines the difference among the mean of three or more groupings/attributes).

Anytown Example

Once you have collected data from your respondents, you can tally and rank factors that respondents said regarding their shopping preferences and behaviors. Specifically, you can tally and rank them by demographic attribute (age, income, education, etc.) to see differences within the population. You can use this information to propose demographic-specific business development opportunities. Depending on how sophisticated you want to be in interpreting data, you may run regression analysis to estimate, for example, the relationships between the various determinants of where people shop and why they shop there. You may find that the statistical results reflect the qualitative responses of your sample and you are now ready to write your report.

Communicating Results

You can tailor the communication of the results of your survey to different audiences. For example, a short news release with key information should be sent to the local media outlets. A more comprehensive report should be made available to downtown business operators. You may consider a policy brief for an audience concerned with that type of interpretation. Consider the audience as well when including charts and tables explaining the results and their implications.

Closing Thoughts

Like all social science research, you must administer your survey in ways designed to avoid risks to the respondents, participants, and interviewers. Federally-funded research must meet certain criteria for the protection of human subjects. It’s a good idea to follow these criteria even if your research project is not federally funded.

Finally, findings from your consumer survey should be integrated with other elements of your market analysis. The results of your survey of consumers help shape other components of your research.

About the Toolbox and this Section

The 2022 update of the toolbox marks over two decades of change in our small city downtowns. It is designed to be a resource to help communities work with their Extension educator, consultant, or on their own to collect data, evaluate opportunities, and develop strategies to become a stronger economic and social center. It is a teaching tool to help build local capacity to make more informed decisions.

This free online resource has been developed and updated by over 100 university educators and graduate students from the University of Wisconsin – Madison, Division of Extension, the University of Minnesota Extension, the Ohio State University Extension, and Michigan State University – Extension. Other downtown and community development professionals have also contributed to its content.

The toolbox is aligned with the principles of the National Main Street Center. The Wisconsin Main Street Program was a key partner in the development of the initial release of the toolbox. One of the purposes of the toolbox has been to expand the examination of downtowns by involving university educators and researchers from a broad variety of perspectives.

The current contributors to each section are identified by name and email at the beginning of each section. For more information or to discuss a particular topic, contact us.